ETHIOPIA

1975-1979

Introduction and photo gallery

An account of the work and travels of Charles Emile van Santen

Agricultural economist during his assignment to the

Ethiopian Settlement Authority

Bogor, Indonesia

2010

Contents

Introduction

A. Ethiopia: The rural situation during the 1970s and before

1. Background Information Ethiopia

2. The rural situation in Ethiopia in the 1970s

2.1 The Northern Highlands: The Amharic and Tigray

2.2 The Southern Highlands: The Oromo and Sidamo

2.3 The eastern low lands: The Afar

2.4 The south eastern lowlands: The Somali

3. The regime of emperor Haile Selassie 1930-1974

4. The 1970-1974 drought and famine in Ethiopia

5. The 1974 Ethiopian revolution

B. Settlement of landless rural population

6. The need to settle landless in the lowlands

7. Government and Non-Government settlement organizations

8. The National Ethiopian Settlement Agency

9. The 1975 Settlement Study

9.1 The landless Ethiopian rural population

9.2 Description of the six settlement case studies.

10. Summary of conclusions and recommendations

Annex

1. The Konso

2. Living in Addis Ababa during the Revolution 1975-1979

3. References

3.1 General

3.2 Technical reports on settlement of rural landless

3.3 The Charles van Santen Image Collection: Ethiopian chapter.

INTRODUCTION

The following report is an account of my work from 1975 to 1979 in Ethiopia, to which country I was assigned by FAO, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations Development Programme as an agricultural economist of the Settlement Agency of the Ethiopian Government. My main responsibility during this period was conducting a national study of existing land settlement schemes for landless rural populations.

During this period Ethiopia was engaged in a civil war, which was fought between a ruthless Marxist regime and Ethiopian Non Marxists groups. From 1977 onwards the country was also engaged in a war with Somalia, mainly because of a dispute about the division of water from the Wabi Shebella River in the Ogaden.

The continuing civil war and the war with Somalia during the 1970s restricted the movements of Ethiopians and foreigners alike and people were not allowed to travel outside the capital Addis Ababa. Fortunately our settlement study team obtained special travel permits to survey the approximately 100 settlement schemes existing at that time in Ethiopia, most of which were located in remote areas.

Due to these travel restrictions the Ethiopian photo gallery and introduction to my work covers only my work and travels for the national Ethiopian land settlement study. The study offered me the only occasion to travel outside the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa. The Ethiopian chapter of my professional work and travels is therefore more limited in set up compared with the other chapters of my web site, which also include accounts of private travels.

I am fully aware that interest in settlement of landless rural population is limited to development professionals working in land settlement projects. However, it is my personal opinion that it is important that the information and images, collected by me in Ethiopia during 1975-1979, are recorded and preserved for future generations. I was one of the few professionals in those days, who had access and detailed information on settlement issues in Ethiopia. I thus find it my duty to write this account aware of the fact that these issues had a major impact on rural development in Ethiopia. Furthermore my experiences may have relevance for other countries in similar stages of development.

My account is based on my reports and other relevant references, which are listed in Annex 3.

The following account describes first the desperate situation of the small farmers in the rural areas of Ethiopia before and during the early 1970s, which was caused by feudal land tenure conditions existing at that time in Ethiopia. Unfortunately the severe drought of 1970-1974 worsened the situation and an estimated 200 000 rural people died in Ethiopia due to starvation while most farmers during this period lost all their crops and livestock. The second part of my account describes the response to this situation which lead to the establishment of settlement schemes aimed at improving the situation of the rural landless.

A. ETHIOPIA: THE RURAL SITUATION DURING THE 1970S AND BEFORE

1. Background Information

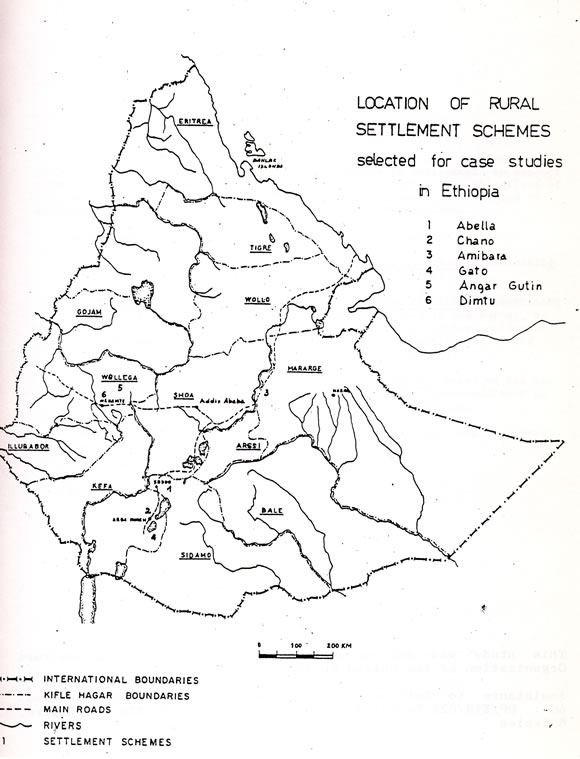

Ethiopia, a landlocked country, is situated in the Horn of Africa. (See Image- 000: Map of Ethiopia.) It is bordered by Eritrea in the north, Sudan to the west, Kenya to the south, Somalia to the east and Djibouti to the northeast. Its size is 1 100 000 km2, which implies that Ethiopia is the 27th country of the world by size. In the early 1970s its population was estimated at 24 million inhabitants. The 2007 population census recorded that the Ethiopian population had increased in that year to 85 million inhabitants. The capital of Ethiopia is Addis Ababa.

Ethiopia is one of the oldest countries in the world and Africa’s second most populous country. The oldest hominid remains of the world were found in Ethiopia and have been dated at approximately 3 million years ago.

Jumping to historical times, there is evidence of a Semitic speaking people in Ethiopia and Eritrea at least as early as 2000 BC. Amharic the official Ethiopian language belongs to the Semitic language group. Some historians assume that the country was settled round 1100 BC by Sabaean people arriving from present day Yemen and Ge’ez, the ancient Semitic language of Ethiopia is assumed to be derived from the old Sabaean language. However, other historians assume that the first Ethiopian civilization had a true African origin.

Ethiopian dynastic history began with the reign of Emperor Menelik 1 in 1000 BC and continued via the Aksumite Empire from the 4th century AD till the 20th century. The last emperor was Haile Selassie I, who was removed from power in 1974. Today the Amharic form 27% and the culturally related Tigray form 6% of the Ethiopian population. However, due to their important role during Ethiopia’s history, they are considered the most dominating and influential population groups, which explains why Ethiopian’s national language is Amharic.

Initially the country only covered the northern part of present day Ethiopia, but since the 19th century Ethiopia has gradually expanded in the south to the borders of today.

The Europeans considered Ethiopia, during the last two thousand years, as the mysterious country of Prester John, a saint and a king. Several European countries invaded Ethiopia during the 19th and 20th century. In 1868 a British army made an expedition into Ethiopia to free European prisoners from the emperor Tewodros. Italy, which had planned to conquer the country in the 1890s, was badly defeated during the battle of Adwa in 1896 by the Ethiopian army under Emperor Menelik II. Ethiopia was brutally occupied by Benito Mussolini’s Italy from 1936 to 1941, ending with the liberation by British forces in 1941.

Ethiopia was the second earliest country to adopt Christianity during the fourth century AD, after Armenia. Christianity was in 316 AD introduced to Ethiopia by Meropius, a Christian philosopher from Tyre, in present day Lebanon. Some years later St Frumentius of Tyre also called Abba Selama-Father of Peace, converted King Ezana from the Aksum kingdom. Since then the Amharic and Tigray populations of Ethiopia have been Orthodox Christians under the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, which is related to the Coptic Church from Egypt. Actually, till 1950 the Ethiopian patriarch, or Abuna, was sent by the patriarch from Alexandria, Egypt. Today about 65% of all Ethiopians are Christians, among which over 80% of the Amharic and Tigray population. The rock churches of Lalibela and other locations contain beautiful rock paintings, dating from the 12th century and are well known.

Since 640 AD there has been a considerable Islam minority in Ethiopia. Today about 35% of the population is considered to be Muslim. Harar, located in the Ogaden, is the holy Muslim town of Ethiopia.

The Oromo, the Sidamo and other Cushitic speaking people, who originally lived in Kenya, have migrated to Ethiopia since the 16th century. These Cushitic speaking people gradually occupied the southern half of the country. Today the Oromo form the largest cultural group of Ethiopia with 35 % of the population.

Ethiopia is one of the world’s genetic centers for agricultural crops:

According to today’s generally accepted theory of the Russian biologist Vavilov, all agricultural crops were first cultivated and selected in one of the world’s genetic centers, from where these crops were gradually spread to other parts of the world. According to this theory, one finds in the genetic center of a specific crop, the largest genetic variation between the different landraces of this particular species. Ethiopia is an important genetic centre which contributed the following important agricultural crops to the world:

- Coffee- Coffee Arabica. See images: Images: 160-163,179

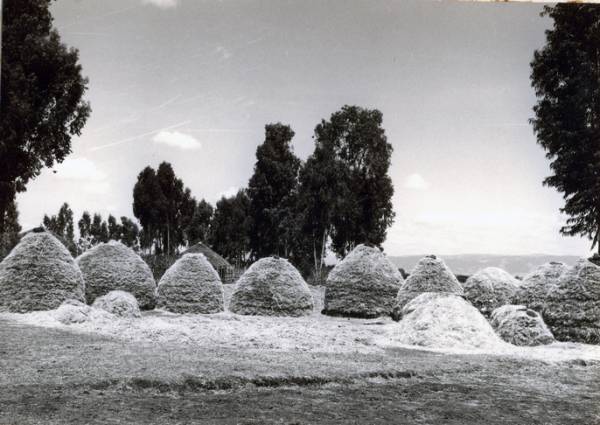

- Teff- Eragrotis tef. Teff is the main Ethiopian cereal crop used for baking of a flat type of bread, which is called injera and is therewith the main staple food of the Ethiopians. Teff is a very healthy food: high in protein, calcium, phosphorus, iron, copper and aluminum.Images:140-141,341-344,410-411,465-467

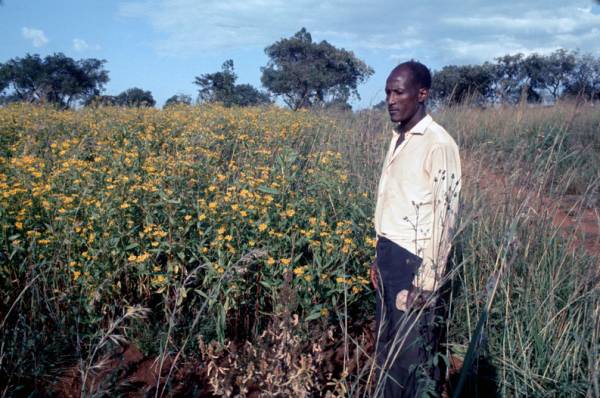

- Noug-Guizotia abessynia, an oil crop which produces 50 % of the Ethiopian vegetable oil needs Images:154-156

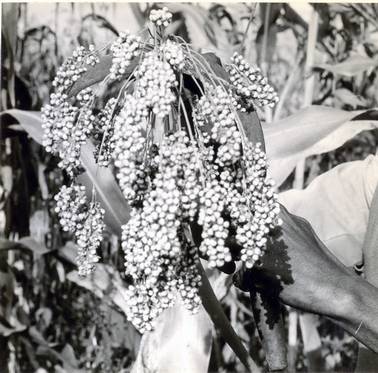

- Sorghum-sorghum bicolor, a cereal crop, particularly grown in South Ethiopia. Images=146-151

- Sesame-Sesanum indica, an oil crop. Though the main sesame genetic center is found in India, it is assumed that Ethiopia is the secondary genetic center for this crop. Images =152-153

- Ensete ventricosa- False Banana. Ethiopia is also a secondary genetic center for this crop. Flour is made from the pseudostem and corns of Ensete, which are being fermented for several weeks and used for making a type of flat bread.Image=480

2. The traditional rural situation in Ethiopia in the early 1970s

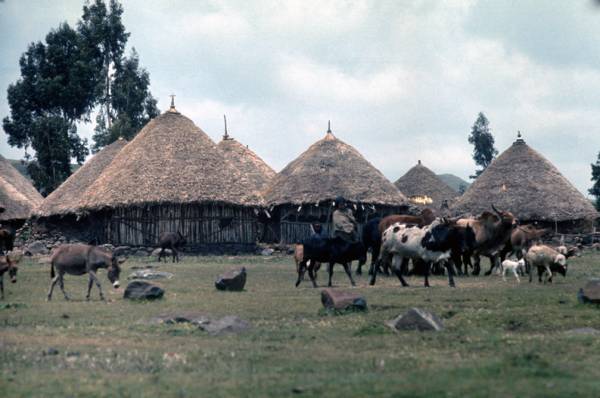

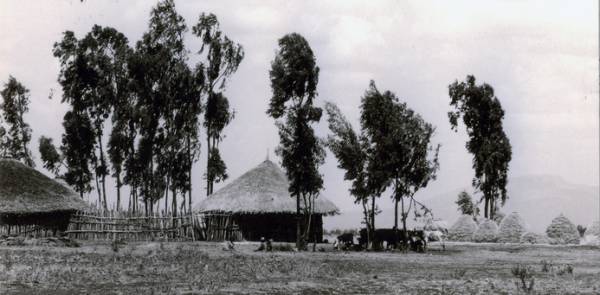

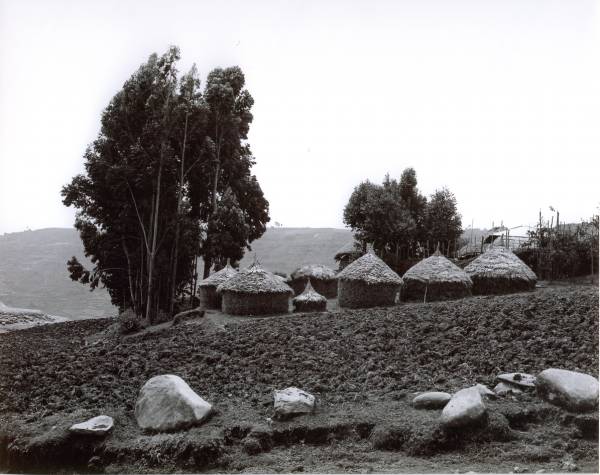

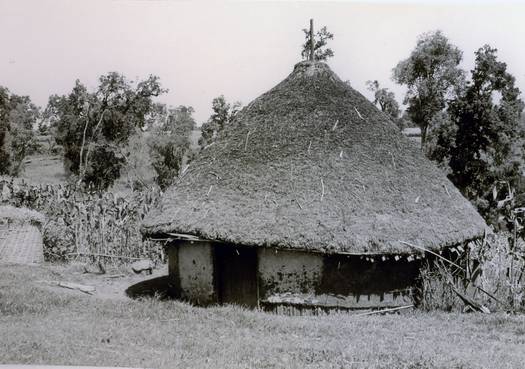

Up to the 1970s, Ethiopia was a very traditional country with over 90% of the population living in the rural areas. The Ethiopian population, estimated in 1970 at about 24 million, was mainly living in the Ethiopian Highlands at the altitude zones of between 1700 m to 2200 m above sea level.

Till the 1974 revolution Ethiopia was a feudal country, in which most of the agricultural lands were owned by absentee land lords, who maintained a harsh control over their land. After the 1974 revolution all landownership was abolished, and since then farm families can only obtain land use titles for a period of maximum 99 years, with a maximum holding size of 10 ha, which title can only be transferred to their direct heirs. Sales of these land titles are not allowed.

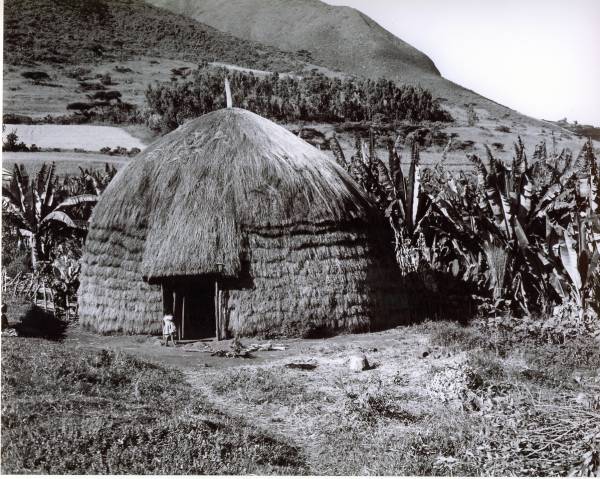

Up to 1974 90% of the Ethiopian population were traditional farmers, operating small mixed farms with an average farm size of 2 ha, growing traditional subsistence crops including teff, barley, hard wheat and sorghum as cereal crops; noug and sesame as oil crops and legumes such as red beans, while in some parts of the Southern provinces maize, millets and sorghum replaced teff and barley. Most farmers kept a pair of plough oxen. In addition they owned some sheep and goats. Milk of cattle, sheep and goats, forms an important part of the Ethiopian diet. Some of the well to do farmers also owned a horse. A majority of the farms were located on erosion prone steep slopes. The Sidamo, living in the highlands of Gamu Gofa, grow in addition Ensete- Ensete ventricosum, the false banana, of which the pseodo stam produces a nourishing flour.

2.1 The Northern Highlands: The Amharic and Tigray

The Amhara and the Tigray, who live in the highlands of the Northern provinces Shoa, Wollo, Gojam, Begemder and Tigray are Semitic speaking people, who arrived in Ethiopia at about 1000 BC from South Arabia, pushing out, or absorbing the original Hamitic population of these areas. They were the founders of the Aksumite kingdom.

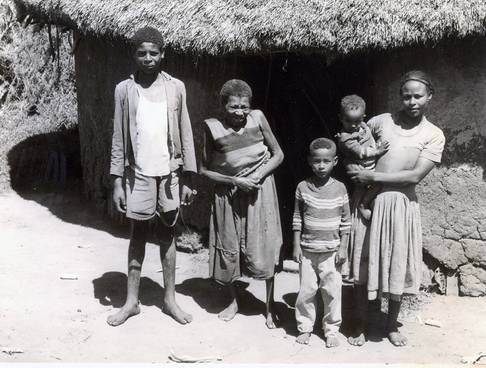

All farmers in these provinces possessed a traditional title to the land known as rist, as members of their kinship group. The rist land title was hereditary, inalienable and inviolable and could not be lost through absence from the land. The higher local aristocracy and the senior members of the Ethiopian church clergy had received in their area the right of gult for all the rist lands from the emperor, mainly as compensation for their services in lieu of salaries. This gult entitlement included the right to collect the land tax on behalf of the emperor, whereby the gult holders were allowed to keep up to 50 % of the rist tax as compensation. Most of the aristocratic and clergy gult holders were absentee landlords. They were very strict in collecting the land rent through their agents even during famine periods. Before the 1974 revolution farmers were easily evicted if they could not pay their land tax and the rist title to the land was taken by the land lord, who always was also a member of the same kinship group. Due to this system many farmers lost their rist entitlement to the gult holder, the landlord. It is estimated that by early 1970s nearly fifty percent of the farmers in North Ethiopia were tenants. The population of the Wollo and Tigray highlands in 1970 was estimated at 4.2 million people. Images:210-238, 281-300, 320-325, 401-426

2.2 The Southern Highlands: The Oromo and Sidamo

The situation in the Southern provinces was very different. The Oromo and Sidamo and some related smaller ethnic groups, who are all speaking Cushitic languages, have occupied the Southwestern provinces of Ethiopia since the 16th century: Wollega, Illubabar, Kaffa, Arussi, Sidamo and Gema Gofu. Originally, these people came from North Kenya, in which country they were still pastoralists. Since then the Oromo and related groups have gradually adopted crop production and in the twentieth century farm similar traditional mixed farming systems as the Amharic and Tigray farmers in Northern Ethiopia with traditional subsistence crops such as: sorghum, barley, wheat, maize and millet, oils crops: noug and sesame and legumes: red beans, while the Sidamo in addition grow ensete, the false banana. The Oromo and Sidamo also own livestock: cattle, sheep and goats.

During the second half of the 19th century these Southern provinces were gradually conquered by the Amharic emperors. After having been conquered, two thirds of the lands were directly taken from the traditional farmers and given to civil servants and clergy from the Northern provinces as compensation for their services to the emperor. The Ethiopian economy was still traditional and in the absence of mining or industry, the only way the emperor was able to compensate his former senior civil servants, was to give them an entitlement in land, mainly in the southern Ethiopian provinces, which land was regarded by the Amharic as new land recently conquered. All land in the Southern Ethiopia provinces was considered Government owned land by the Amharic. In this view, the Oromo, Sidamo and other traditional cultural groups, living in the Southern provinces, were assumed to possess only temporarily customary land entitlements, in spite of the fact that many Oromo and Sidamo farmer groups had farmed these lands for at least the last few hundred years, since arriving in Ethiopia after the 16th century from Kenya.

Haile Selassie, since becoming emperor, actually increased handing out land to his loyal former senior civil servants. Initially, these land lords did not disturb the traditional farmers from the Southern provinces, as long as farmers paid their land tax.

However, since the early 1960s many Northern landowners in South Ethiopia had received an education abroad, they wished to develop their lands and establish modern mechanized farming after their return to Ethiopia. It was found that many of these landlords, especially those who had received a foreign education, could easily receive individual assistance from foreign aid agencies. To establish their mechanized farms, there was no place any more for the traditional farmers who were occupying these lands. Many of these landlords were local governors and instructed the police to evict the traditional farmers from their lands.

As a result of the above development by 1974, there were tens of thousands of evicted traditional farmers in the Southern Ethiopian provinces. In 1974 many of these desperate landless rural people, eagerly joined the Revolution started by the students, in an attempt to get their lands back from the landlords backed by Emperor Haile Selassie.

The Oromo form about 35% of the Ethiopian population and about 50% of them are Christians and 50 % Muslim. The Sidamo form 9% of the Ethiopian population. They are mainly animist. In the 1970s the population of the Southern highlands was estimated at 10 million inhabitants. Images: 079-086, 141-165

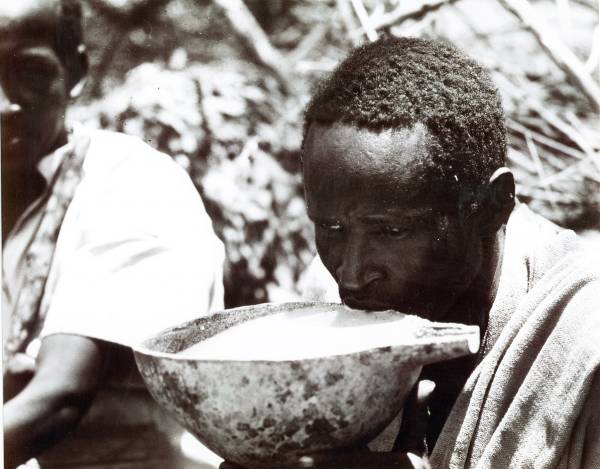

2.3 The lowlands of Eastern Ethiopia: The Afar

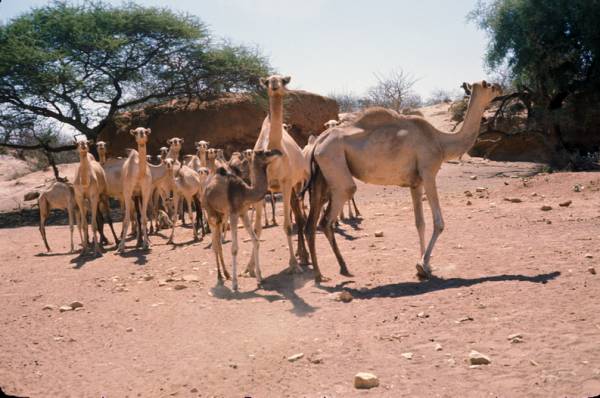

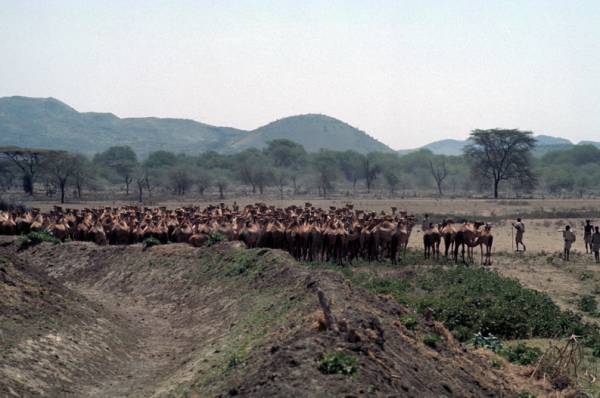

The Afar live in the Eastern lowlands of Ethiopia, mainly in Wollo and Tigre provinces, they are semi nomadic pastoralists who speak a Cushitic language. The Afar own large herds of camels, cows and goats and subsist mainly on blood and milk of their animals. They occasionally barter wool and skins with highland people mainly, to obtain cotton for their clothing. The Afar form about 2 % of the Ethiopian population.

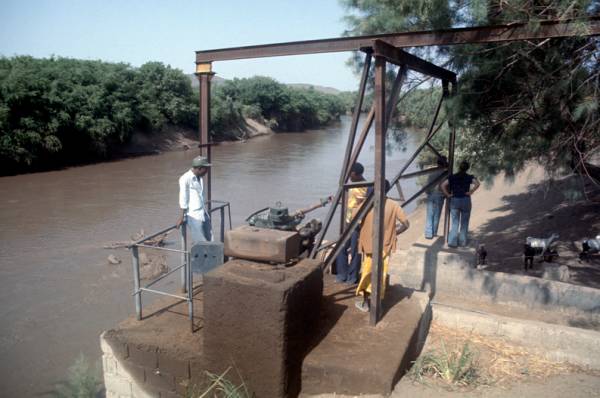

In 1962 the Government established the Awash Valley Authority to promote large scale commercial cotton growing in the flood planes of the Awash River and granted the Mitchell Cotts Group from Great Britain, permission to set up the Tendaho Cotton Plantation Share Company, which company by 1974 occupied the most fertile one third part of the Awash valley for their cotton plantations. This considerably reduced the grazing grounds available to the Afar, causing serious malnutrition among the Afar.

Images: 093-105,111-132,304-318

2.4 The lowlands of South East Ethiopia: The Somali

The Somali live in the South East lowlands of Ethiopia, mainly in Bale province: The Somali, similar to the Afar, are semi nomadic Cushitic speaking people, who also own large herds of camels, cattle, sheep, goats and horses and consume the milk and blood of their livestock for subsistence, occasionally bartering some animals, hides or skins for cotton for their clothing.

Gode Kelafo Project for Somali settlers: Images: 051-070,448-461.

During the long history of Ethiopia local tribal wars and severe drought periods of several years, occasionally disturbed the above described situation. However after these droughts and wars were past, the situation in Ethiopia returned to peace. The above account describes the situation in Ethiopian before the 1970-1974 drought period and the 1974 revolution.

3. The regime of emperor Haile Selassie 1930-1974

Emperor Haile Selassie, who had already firmly established his control over the country since the late 1940s, further increased his control of Ethiopia during the 1960s using the large scale development assistance Ethiopia received from foreign Government- and NGO agencies, among which from the United States and European countries including Great Britain, France, Sweden and the Netherlands.

Using this foreign assistance, the emperor send many young Ethiopian to study abroad, while other technical and financial assistance received, was used to open up the country.

The effect of all this foreign assistance was a rapid increase in population particularly in the already relatively densely occupied northern highlands. The modern medical assistance provided by missionary groups rapidly reduced the infant death rate, which caused a rapid increase of the population resulting in overcrowding of the Ethiopian highlands during the 1970s.

Another issue was that most young Ethiopians preferred to stay in the highlands in traditional farming. This resulted in a much slower development of industries and commercial enterprises compared with most other developing countries, in which countries most young people left the rural areas for the towns. This custom of staying in the highlands on the family farm further added to the population pressure in the highlands.

In summary, the rural Ethiopian situation gradually changed irreversibly since the late 1950s, due to the following factors:

- A rapid increase of the highland population resulting in overcrowding, farm size reduction and erosion damage of farm land, particularly in North Ethiopia.

- Eviction of traditional farmers by new landlords, who had obtained formal deeds to lands in South Ethiopia, which had already been occupied for many years by traditional Oromo and similar farmer groups.

- A sever drought in Northern Africa during 1973-1974 covering most of the highlands and lowlands of Ethiopia.

4. The 1970-1974 drought and famine in Ethiopia

The drought in Wollo and Tigre provinces started in the late 1960s with a number of years with below average rainfall, reducing harvests and leading up to the severe drought of 1973-1974 when rain completely failed. The effect on the small fragile erosion prone, highland farms in Wollo and Tigray Provinces was disastrous. Crop production failed from the 1970 harvest onwards for four subsequent years and by 1973 the livestock started to die in large numbers, as all grazing land had dried out completely. After the farmers had consumed their last food stocks, they also started to die in great numbers. Estimates of victims of the famine ranged from 200 000 to 1 000.000 deceased persons.

In late 1972 a first warning of the seriousness of the drought and famine was given by Christian Missions operating in the Tigray province and by some University researchers, working in the Wollo province. A joint report by FAO and the Ministry of Agriculture dated December 1972, reported a large drought and famine in Wollo and Tigris provinces. The report actually included an estimate of the amounts of grain needed to avoid starvation of large groups of the farming population. Unfortunately the report was completely ignored by the central government, which actually in late 1972 sold a large amount of cereals in storage on the export market.

Struck by the severe famine among the rural population several NGOs gradually started to organize food and shelter posts along the Addis Ababa-Desi-Asmara road. Many desperate farm families from the remote villages in the highlands, who had heard of these food handouts, started to travel on foot to these food and shelter posts along the main road. Some families had to travel over a 100 km to reach these help posts along the main road and many people died during their travel to the main road, struck by severe famine, illness and total exhaustion. From some far away villages there were no survivors at all.

Despite these warnings from missionaries and local government staff the Ethiopian national and provincial Government continued to refuse to recognize the existence of the drought.

Finally a TV presentation on 18 October 1973 on British TV by Jonathan Dimbleby: The Unknown Famine, made the world aware of the seriousness of the famine.

The most striking image of the Dimbleby presentation was a picture of the emperor feeding his lions with large pieces of meat, while telling the reporter that: “There is no hunger problem in Ethiopia. There have always been famines in Ethiopia, which is a normal occurrence in my country. There is no need for negative reports or actions.” The TV presentation of the interview with the emperor was mixed with images of people dead or dying from hunger, taken only a few days earlier in Wollo province.

The effect of the Dimbleby presentation was that the World suddenly became aware of the enormous calamity that had struck Ethiopia. Soon after, Ethiopian and foreign aid agencies started to provide food and shelter and by late 1974 more than 40 aid agencies were operating in Ethiopia to give food and shelter to the Wollo and Tigray rural population. Curiously, initially part of the aid supplies were stolen by some high level Government officials. Another problem was that the Minister of Finance insisted on taxing the imported aid goods with a high rate, as he found these emergency food imports unnecessary. However, due to strong international complaints, finally the Government officials were punished, who had stolen the food aid, and the Minister of Finance stopped taxing the food aid.

In the1974 season it was further reported that drought had also affected the grazing lands of the Afar and the Somali pastoralists. Their only wealth, their livestock started to die in large numbers, depriving these pastoralists of their sole means of subsistence. Fortunately aid agencies were able to follow up this calamity much quicker and food and shelter distribution for the Afar and Somali pastoralists were quickly started. Later also some parts of the Southern highlands were effected by the drought, but by this time the aid organizations were able to act much more quickly.

For the record, it has to be mentioned that indeed Ethiopia has often in the past been suffering from severe droughts and famine in which tens of thousands of people died. Considering only the 20th century, there have been seven severe drought periods before the 1970/74 drought: These were during: 1896-1901, 1913-14, 1920-22, 1932-34, 1953-54, 1957-58 and 1964-66.

Since the 1970-1974 drought, Ethiopia has again been suffering from drought during 1984-1984, 1987-1988, 1994-1996, when the country was ruled by the Marxist regime. The latest drought, during the present regime of Meles Zenawi, was during the period 2000-2003 and again some eight million rural Ethiopians suffered from malnutrition. Unfortunately the response to the calamities by the Marxist and the present regime was hardly better as compared with Haile Selassie’s response.

5. The 1974 Ethiopian revolution

The effect of the deteriorating situation in Ethiopia since the late 1950s including the deteriorating land tenure situation in North Ethiopia and the eviction of large numbers of traditional farmers in South Ethiopia in combination with the severe 1970-1974 drought, can be summarized as follows:

- A rapid increase of the highland population in the Northern Provinces resulted in overcrowding, farm size reduction and erosion damage of farm land.

- Eviction of large groups of traditional farmers by new landlords in the Southern Provinces created a large group of desperate rural landless

- The severe drought in Northern Africa during 1973-1974, covering most of the highlands and lowlands of Ethiopia and other parts of Africa, resulted in severe famine.

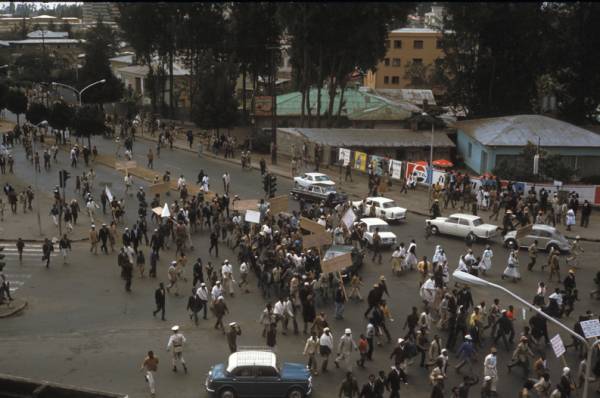

The effect of these negative factors resulted in a great unrest of the Ethiopian population. Thus, in spite of the ruthless control of the emperor, the regime started to break down in January 1974. It started with a mutiny among several army units in January 1974. These were joined by taxi drivers, students, teachers, and other civil servants, who did not longer accept the harsh government rules. Initially, the Haile Selassie regime tried to control the situation, but without success. Encouraged by the success of the first groups of protests, the rural population, in particular the evicted traditional farmer groups in South Ethiopia, joined the revolution, which continued during the following months. By September, however, Marxists elements within the army had gradually taken control of the revolution and increasingly controlled the entire country. The emperor and his senior civil servants, mainly members of the aristocracy, had been put in prison by October and many of these senior civil servants were executed during the following months. The emperor died suddenly in his prison in August 1975 under mysterious conditions. It was claimed that Hail Mariam Mengistu, the leader of the revolutionary Marxist army committee-the Dergue, which had taken control of Ethiopia, had personally killed the emperor in his sleep with a pillow.

NB It is outside the context of this introduction on land settlement to describe in detail the 1974 Ethiopian revolution, which is excellently reported in: “Class and Revolution in Ethiopia’ by John Markakis and Nega Ayele, 1978 to which monograph is referred.

B. SETTLEMENT OF THE LANDLESS RURAL POPULATION

6. The need to settle the landless in the lowlands

The above short overview of the rural situation in Ethiopia described how by the end of 1974 there were millions of destitute and hungry rural landless in Ethiopia, who were fed by national and international Government and NGO organizations, a situation which could only be acceptable on the short term. A more permanent solution was desperately needed, in which rural landless could at least take care of their subsistence requirements.

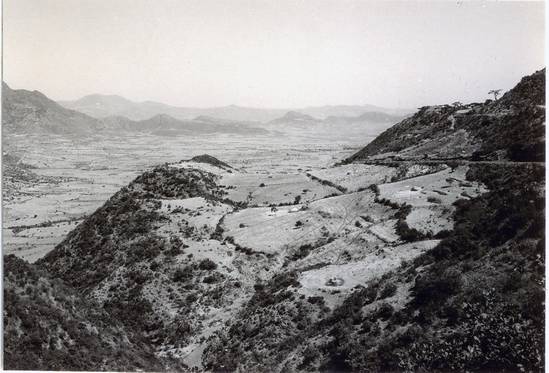

Up till the 1970s 90 % of the Ethiopian rural population, were living mainly in altitude zones of 1700 meters and above, apart from small groups of nomads who lived in the hot semi desert lowlands in the south eastern provinces. In the early 1970s’ the actual farm land of Ethiopia in the highlands was estimated at between 5 to 7 million ha or less than 7% of the Ethiopian territory, but population densities in the highlands were high and ranged between 200 to 400 persons per square km. In 1974 possibilities to improve the situation of the rural population in these eroded over crowded highlands were completely exhausted. The situation had been further deteriorated by several years of severe droughts particularly in the highlands of North Ethiopia, which had resulted in total crop failures and the death of most livestock and an estimated 200 000 famine deaths and hunger for the surviving local population, while in southern Ethiopia the situation had further deteriorated, due to the emperors’ policy to compensate his senior civil servants with deeded land in these highlands. These former civil servants had developed mechanized farming and evicted thousands of traditional subsistence farmers from their land which had created a large number of destitute rural landless. The solutions therefore had to be found outside the highlands.

In 1974 there were no employment opportunities in other sectors of the economy, as at that time, industry, commercial enterprises and mining enterprises were hardly developed and absorption of large numbers of destitute rural landless was not feasible in these sections of the Ethiopian economy.

The only option available was thus to settle the rural landless in the lowlands on suitable farm land, allowing them to produce their own food and other subsistence needs and if possible, to create some opportunities for further improvement of their lot. Before the 1970s most of the Ethiopian lands below the 1500 meter zone were uninhabited and undeveloped, because of the following disadvantages:

- Infestations of malaria effecting human and trypanosomes-sleeping sickness affecting livestock.

- Sub-marginal rainfall patterns, requiring expansive irrigation systems for crop production

- Low accessibility- no roads, nor other physical and social infrastructure.

Preliminary surveys conducted during the 1960s and early 1970s in the Ethiopian lowlands, however, indicated that large stretches of uninhabited land were available which contained well drained fertile soils and suitable rivers for irrigated agriculture. Estimates indicated that from 9 million to 16.7 million ha of suitable farmland was available below the 1500 m zone, mainly in the Southeastern provinces of Wollega, Illubabor, Kaffa and Gamu Kofa. Opening up these lands could easily double the actually cultivated land of Ethiopia provided the above disadvantages could be overcome.

However, to develop these lands for smallholder foodcrop farming a systematic effort would be necessary to build up an adequate infrastructure for crop and livestock production, including the establishment of access roads, land development, establishing irrigation and drainage systems and other economic and social infra structure. Development of these lands for settlement could therefore only be implemented by formal development agencies, such as Government and Non Government Organizations, which had access to sufficient finances, technical resources and development expertise, in order to overcome the physical and financial disadvantages of these low lands. There was little scope for spontaneous settlement by individual farm families.

7. Government and Non-Government settlement organizations:

Their tasks and responsibilities

The introduction of a settlement agency to develop these lowlands is therefore a basic requirement for rural settlement in the lowlands of Ethiopia, regardless if the settlement agency would be an NGO, a Government Agency and locally or internationally supported with funds and expertise.

Implementation of settlement schemes involves infrastructure; agricultural production; credit, marketing and supply systems; social services and settler and staff training.

In detail the following issues are required by a settlement agency to successful

operate settlement schemes:

- Establishment of objectives of the settlement projects including reasonable minimum settler family income levels.

- A physical survey to evaluate the potential land available for the project

- Preparation of project plans and designs

- Identification, selection and training of settlement agency staff

- Identification, selection and training of settler families

- Implementation of land clearing, land development and the establishment of basic infrastructure: roads, irrigation and drainage systems and service centers for supplies of agricultural inputs and the marketing of agricultural produce, including credit schemes for financing agricultural inputs; schools, clinics and other infra-structural services.

- Preparation of farm plans including the calculation of optimal farm size, farming and livestock systems.

- Establishment of services for settlers including training and farm credit

- Establishment of the legal obligations for settlers viz a viz the settlement agency.

- Soil conservation measures

- Control of malaria and trypanosomes

- Other relevant social services

- Obtaining finances for the implementation of the above.

8. The National Ethiopian Settlement Agency

In late 1973 a joint effort from Ethiopian NGOs and progressive elements in the Ethiopian Government established the Ethiopian Relief and Rehabilitation Commission, a semi government agency. Some of the senior RRC staff anticipated that after the emergency period of giving food aid to the millions of landless farmers, a follow-up had to be organized to help these destitute landless rebuilding their lives and help them with farmland to enable them to produce their own subsistence needs. It was anticipated that many refugees would not be able to return to their former homes, as they had lost their land or their land was completely degraded. There was, therefore, a need to settle these landless somewhere else in Ethiopia.

To support these ideas a Settlement Commission was established within RRC, with the task to coordinate existing and future agencies, who intended to settle landless people.

Rapidly, further developing the RRC Settlement Commission, in early 1974 technical assistance was requested from the United Nations Development Program, UNDP. Subsequently this UN agency asked FAO to organize a project to assist the RRC Settlement Commission. In late 1974, I was assigned to this project as its agricultural economist, with the task to develop socio economic guidelines for settlement agencies.

After my arrival in Ethiopia in early 1975, I was informed of the existence of a number of existing settlement schemes, some of which already had been established since the 1960s, to settle landless farmers and ex lepers in different locations of Ethiopia, by a number of government and NGO organizations.

We therefore conducted a preliminary survey among aid agencies present in Addis Ababa. This survey indicated that in early 1975 there were already at least 50 settlement schemes existing in Ethiopia, of which the oldest was established in 1958 for for destitute highland farmers in Abella-Wolaita in South Ethiopia. The initial survey showed, however, that little substantial information was available in the headquarters of the various agencies in Addis Ababa, as most of the headquarters staff were mainly involved in food aid to the destitute Wollo, Shoa and Tigray populations.

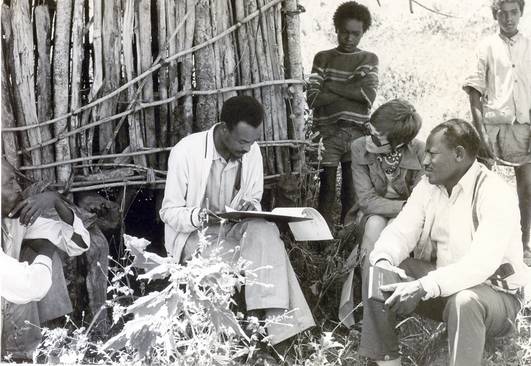

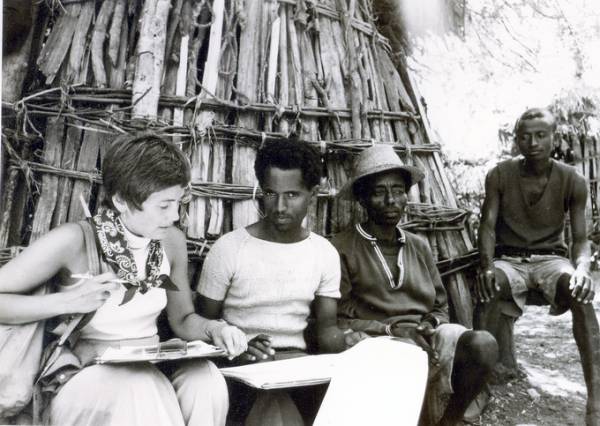

Based on my tentative findings the RRC Settlement Commission decided to conduct a National Ethiopian Settlement Study, using available Government research staff supported by FAO staff and I was appointed as director of the study for this national Ethiopian settlement study.

9. The 1975 Settlement Study

The purpose of the 1975 national settlement study was to collect information about all existing and planned settlement schemes, regardless if these had been organized by Government or Non Government Agencies, with the support of national or international sources. The main objective of the study was “To offer guidance to settlement development in Ethiopia” based on the experiences of existing settlement agencies and settlement schemes.

The initial field work for the survey was conducted in 1975, during which period all existing settlement schemes and most of the sites planned for new settlement schemes were visited, covering all reported settlement agencies established in Ethiopia by 1975.

The information collected during this survey showed that in 1975 there were 97 settlement schemes in Ethiopia with 50,465 settler families, while another 35 schemes were in the process of being established for some additional 20,000 settler families.

After processing of the data collected during the initial field survey, the following four main categories of settlement schemes were identified:

Overview of the four main categories of Ethiopian settlement schemes

| Categories of schemes | Description of basic features |

| 1.Self help subsistence | The production level in these schemes is set to provide the settlers with means to obtain basic subsistence.

This was set at 1500 kg of cereals for an average family of 5 persons per year or 820 grams of cereals per day, sufficient for basic survival. Most of these settlement schemes were established as an emergency arrangement to help people who were destitute, as a result of the prolonged drought. By 1975 there were 40 settlement schemes in this category with a total of 11 500 settler families or 300 families per scheme, organized by 12 different settlement agencies, some of which were government and some were private agencies. |

| 2.Improved subsistence | The production level set in this category is to provide settlers subsistence and some marketable food surplus to allow them to gradually improve their situation. By 1975 there were 42 schemes in this category of which 35 projects organized by the Settlement Authority and 7 schemes under the responsibility of other agencies with a total of 21,400 settlers families. |

| 3.Modern smallholder farming | The production level set in this category is to provide settlers with full subsistence and at least 30-50% surplus of agricultural produce to be marketed to improve the settlers’ income. By 1975 there were 5 projects in this category organized by four settlement agencies, with a total of 2,648 settler families. |

| 4. Large scale mechanized production oriented schemes based on irrigated agriculture | The production level set in this category was to produce cash crops for export. The settlers’ role was mainly as workers, who received a cash income to cover subsistence and improve their living conditions. There were 3 schemes with 1,433 settlers organized by 2 agencies |

In addition, the survey collected information on five schemes in which lepers were settled with 3,484 settlers by four agencies (Image 42) and two schemes for refugee settlers from the Sudan with 10 000 settlers organized by the UN office of the High Commissioner for Refugees.

Based on this information the RRC settlement commission decided to conduct a second round of field work to study in more detail the following six schemes representing the four main categories of settlement schemes:

| Type of scheme | Name of scheme | Province | Agency | Year established | No of settlers | Ethnic group |

| 1.Self help Subsistence | 1.Gato

2.Chano |

Gema Gofa | MNCD

Min of Nat Community Development |

1972

1970 |

65

300 |

Sidama/Konso |

| 2.Improved subsistence | 3.Dimtu | Wollega | ECMY Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus | 1971 | 200 | Oromo |

| 3.Modern smallholder farming | 4.Abella

5.Angar Gutin |

Sidamo

Wollega |

WADU Wolaita Agricultural Development Unit

SED Solidarité et Développement |

1958

1971 |

984

55 |

Oromo &

Menz-Amharic Oromo |

| 4 Large scale farming | 6.Amibara | Hararghe | Awash Valley Development Authority | 1967 | 409 | Afar |

The following definitions of a settlement scheme and related concepts are used in this report:

A settlement scheme is a development project, which involves the planned movement of people to areas of under utilized potential.

- The concept project is defined as any organized attempt to introduce change

- The more restricted term of resettlement is included in settlement

- The under utilized areas, may include virgin lands or lands with a very extensive land use, such as grazing or shifting cultivation

- Development projects on lands already intensively used are excluded

- The concept includes both rain-fed and irrigated schemes

9.1 The landless Ethiopian rural population

Categories of settlers

A: Peasants: Landless, former evicted tenants, agricultural laborers and traditional farmers. These were mainly traditional farmers from overcrowded highlands or who had been recently evicted by landlords who were developing mechanized farming. In most cases these farmers had a considerable experience with traditional farming methods and were familiar with ox-ploughs, utilization of manure and crop rotation.

B: Nomadic or semi nomadic groups of people: pastoralists and shifting cultivators. These groups were considered for settlement when effected by drought and most of their livestock was lost, or when national interest required a more intensive land-use of areas so far used by these groups for extensive grazing or shifting cultivation only.

C: Urban unemployed and former lepers

Some of these were familiar with rural skills; however, the majority had no rural skills but had been employed previously as craftsmen-carpenters, masons, blacksmiths or as unskilled labor. In addition there were settlement schemes for rehabilitated lepers and for internal and external refugees in Ethiopia during the 1970s.

Preliminary surveys in the Ethiopian lowlands had shown the existence of large stretches of fertile land in the altitude zones below 1700 m suitable for settlement, particularly if irrigated agriculture could be established. Fertile land was available in abundance in areas without sufficient rainfall but with large permanent rivers, suitable for irrigated agriculture. Estimates ranged from 7 to 16 million ha of available suitable land, development of which would at least double the cultivated area of Ethiopia, which was estimated at only 5 to 7 million ha in the early 1970s.

The need for formal settlement agencies in the case of Ethiopia.

There are many examples of traditional societies in the past which developed fertile lands for irrigated agriculture when rivers were available but local rainfall insufficient for crop production. Referred is to the large scale irrigation systems developed in the past by:

- The Sumerians during the Third Millennium BC.

- Civilizations in Egypt, Indus Valley, China, Turkey, Palestine and Cypress during the Second Millennium BC.

- Asian civilizations since the First Millennium BC.

- The Italian irrigation systems in the Po valley established during the middle ages.

- Land reclamations established in the Netherlands, North Germany and on the East Coast of England, since the middle ages. In these reclamation areas, land was reclaimed from the sea, involving dykes and drainage systems, called polders.

In all these examples traditional societies, long before the present day industrial period, managed to design, construct and utilize irrigation systems in river basins or reclaim land from the sea. These societies all managed to organize the many complex issues involved in such engineering work: mobilizing the people, develop and implement the technology as well as arrange the legal aspects and other related issues of such undertakings, which were all organized within the capabilities of traditional societies.

Opening up the fertile lowlands of Ethiopia for irrigated agriculture would involve similar activities: mobilization of the people, development of the technology, arranging the organizational and legal aspects.

Unfortunately, the destitute Ethiopian rural highland population and the Afar and Somali pastoralists did not have the strength and organizational and technical knowhow to open up these lands for agriculture like the above civilizations had done in the past. It was therefore necessary for outside settlement agencies to take the initiative, organizing funds, technologies, organizational structure and selecting settler families.

9.2Description of the six case studies

A short summary of the main aspects of the six case studies:

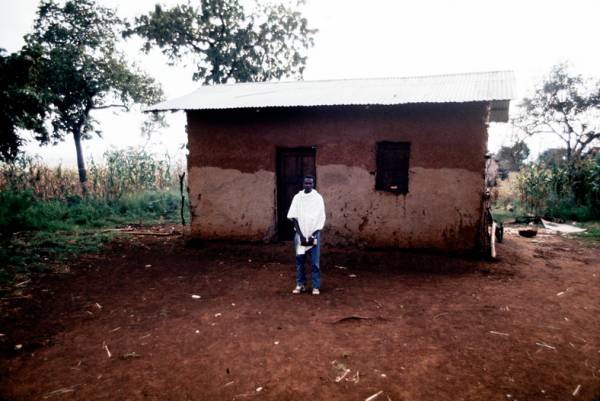

- Gato, a self help subsistence scheme.

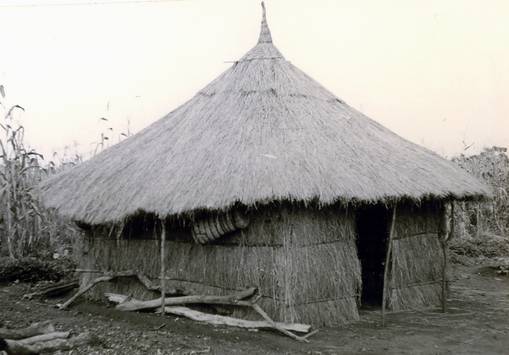

Gato, a self help subsistence scheme, is located at 1300 m altitude, 60 km south of Arba Minch in the Gamu Gofa province.- Gato was established in 1972 by the Ministry of National Community Development: MNCD, for farmers who had lost their land in the Menz area, Shoa Province, 800 km north of Gato.

- All settlers were familiar with ploughing with oxen and traditional farming techniques before migrating to Gato.

- In 1976 there were 65 settler families, who had received a plot of 20 ha, but most settlers had only cleared one to two ha which they farmed twice a year. MNCD, which in addition of provided land and transport of the settlers from Menz to Gato, had only provided an irrigation supply canal of 600 m length from the Gato river to the project area. None of the settlers had received any of the other assistance promised by MNCD. The 65 families owned between them 25 pair of plough oxen.

- The farming system consisted of 1 ha maize and 0.2 ha cotton during the first crop season and 0.5 ha teff and 0.2 ha pepper during the second crop season.

- The total average cash returns per settler family was estimated at $ 190, of which $160 was earned from the sale of crops and $ 30 from the sale of livestock produce, while farm produced, home consumed produce, was estimated at a value of $ 65 per annum per settler family.

- The settlers’ main problems included insufficient supply of irrigation water and the absence of a nearby market center and clinic; malaria is endemic in the area.

- In spite of the lack of support from MNCD the Menz settlers in Gato were optimistic about the future. They hoped that they could improve the situation themselves as the potential situation in Gato was much more promising compared to the eroded land they had left in the Menz area. Images: 081-092,133-145

- Chano, a self help subsistence scheme

Chano, a self help subsistence scheme, is also located at 1300 m altitude, at 10 km north of Arba Minch in Gamu Gofa Province.- Ghano was established in 1970 by MNCD for farmers from the overcrowded highlands in the Gamu Gofa province, who had lost their land. Settlers were Ochollo, Wolaito and Guji subgroups from the Oromo.

- All settlers were familiar with ploughing by oxen and traditional farming techniques before migrating to Gato.

- In 1976 there were 300 settler families, who each who had received a plot of 3 ha, of which 1 ha was irrigable and 2 ha rain-fed, plus a homestead plot of 0.1 ha.

- MNCD in addition to providing the lands, had constructed a 500 m long irrigation supply canal from the Hare River to the project area and given temporary shelter and food support for one year, in the period before the settlers managed their first harvest and had constructed their houses. Most settlers owned a pair of oxen for ploughing.

- The 1 ha irrigated plots were continuously cropped with a rotation of maize, sweet potato and cotton, while the 2 ha rain-fed plots were cropped with maize and sweet potato, during the rainy season. The homestead plots were planted with banana, ensete, citrus and spices.

- The total cash return per settler family was estimated at $ 310, of which $270 from crops, $ 15 from the sales of livestock produce and $ 25 from the sales of fruits. Farm produced, home consumed produce was estimated at $ 70 per annum per family.

- The settlers’ main problems included the poor condition of the irrigation supply canal and the access roads; the absence of a clinic- especially as malaria was endemic in the area, the absence of a flour mill and a market center were also considered as problems.

- Another problem was the group of 257 “dependant” farmers. These were family members who had originally joined to help clearing the land and building the family houses, but who had stayed on and now also requested farm plots.

- The majority of the settlers stated that their income had increased since coming to Chano and they were optimistic about the future, as conditions were better in Chano compared with the eroded small plots they had left in the nearby highlands at a distance of about 5-7 hours walking from Chano. Images 144-145

- Dimtu, an improved subsistence scheme

- Dimtu is an improved subsistence type of scheme.

- It is located at 1400 m altitude, in the Didessa Valley, about 380 km west from Addis Ababa in the Wollega province.

- Dimtu was established in 1970 by the Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus-ECMY for semi-nomadic Nilotic speaking shifting cultivators-Shankilla, from the border area between Ethiopia and the Sudan and for some landless local Oromo speaking farmers from the overcrowded Wollega highlands.

- Before joining Dimtu, settlers were not familiar with ox ploughing. They used hoe farming for growing, maize, sorghum, millet and cotton.

- It is the objective of ECMY to settle these people and to teach them sedentary farming with ox ploughs.

- Settler families, in addition to a piece of cleared land and food before the first harvest, also received agricultural inputs, health care and education. In 1976 there were 200 settler families, but at maturity of the project in 1978 there will be a total of 400 settler families. Each family received a plot of 4 ha, of which 1.5 ha was cleared and ploughed by ECMY for the first year, while the settler was assumed to clear the balance of the 4 ha plot within 3 to 4 years.

- Each settler also received a share of 6 ha in a communal plot for grazing and firewood. Each settler family further received one ox, farm-tools, seeds and food on credit for a total value of $ 130 which credit had to be repaid in 4 years starting from the second harvest.

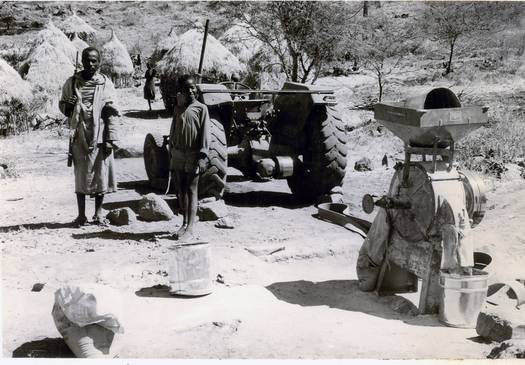

- ECMY further provided settlers with feeder roads, a project center with storage facilities, a work-shop, a clinic especially for malaria treatment, a school and an agricultural extension office, from which each settler family received two visits per week from an extension officer. In view of the trypanosome-sleeping sickness, the oxen and other livestock would be treated regularly against this disease.

- ECMY planned a total investment of about US$ 500 000 for Dimtu, which would be about $ 1350 per ha or $ 5500 per settler family, covering all costs including overheads such as local staff members and one expatriate staff as project leader.

- By 1976 each settler family was cropping 2.1 out of the 4 ha of their plot with 0.6 ha maize, 0.9 ha sorghum, 0.3 ha millet, 0.3 ha cotton and 0.1 ha teff. Net cash returns for the 1975/76 crop year were estimated at $ 200 per family, plus $ 25 from the sales of honey. Settler families spent about $ 70 cash and $ 160 worth of home produced produce.

- Compared with their previous situation farmers found that their lives had been much improved, that their income was higher and that they had access to all basic facilities. Images: 030-038,166-180,184

- Abella, Modern smallholder farming

- Abella is a scheme in the category which aims to develop Modern Smallholder Farming. Abella is located at 1400 m altitude, near the highroad from Soddo to Arba Minch, about 28 km south of Soddo in the Soddo province.

- Abella was started in 1958 and incorporated in 1970 into the Wolaita Agricultural Development UNIT-(WADU)

- Abella was initiated as a pilot project to use the lowlands of the province to reduce the pressure on the highlands in the Soddo province, where population densities of up to 440 inhabitants per km2 existed.

The WADU development strategy included giving emphasis to:

- Land planning and settlement

- Road construction, land clearing, soil conservation

- Provision of water supply

- Establishment of extension services for crops & livestock

- Establishment of marketing cooperatives

- Agricultural Credit arrangements

In 1976 there were 984 settler families in Abella, of whom 85 % came from the nearby overcrowded Wolaita highlands and 15 % from other areas of Ethiopia, among which from the Menz area, about 800 km North of Abella.

- All settlers had previous experience with traditional ox plough farming. All settlers originally lived in the highland, where climates were much cooler and where there was no malaria infestation. Consequently most settlers in Abella suffered from heat and malaria during the first few years.

- The total costs to develop a farm unit in Abella, including development costs and infra structure were estimated at $ 2 000 per 5 ha plot, covering the period 1958-1979. Of this amount 37% was to be repaid by the settlers over a twenty-year period and the balance was a grant, which was financed by the government with loans from the World Bank, the World Food Programme and British Bilateral Aid.

- Settlers received a 5 ha plot of which 2 ha was cleared by WADU and a seasonal credit was given to buy inputs for an amount of $ 150 per unit. In addition, settler families received food aid for the first 12 to 16 months of their stay, till the time of the first harvest and the building of their house was completed.

- Further services included a system of feeder roads:186 km; an agricultural service center; a cooperative consumer store; clinics; schools; a domestic water supply and an agricultural research sub center. The extension officer would visit each settler family twice weekly, whereby one officer would be s responsible for 60 settler families. Further a livestock improvement programme was established to vaccinate the cattle against CBPP, rinderpest, anthrax, black leg and for improved breeding. A main constraint for the settlers is malaria.

- The 5 ha plot included 3 ha for crops and 2 ha for grazing, but most settlers farmed nearly the entire 5 ha plot and cattle were thus forced to graze outside the project boundaries, which was a constraint. During 1975/76 each settler had cropped 3.33 ha cropped of which maize on 1.82; cotton on 0.84 ha, teff on 0.94 ha and red peppers on 0.28 ha

- Net returns from crops was $ 460, from livestock $60; from honey collecting $ 10.

- The average settler owned a herd of 6.4 cattle.

- The annual cash expenses per family for 75/76 amounted to $ 255 and the value of subsistence, farm produced, was estimated at $ 170.

- Most settlers found that their income had increased when compared with their former situation.

- The main problems faced by the settlers were malaria, wild animals, shortage of fire wood, insufficient grazing land, declining soil fertility due to continuous cropping. The farmers also would need more schools and a clinic.

- Some of the dependants who helped in the initial period to clear the plots and build the house now requested a plot of land in line with the new 1975 law on public ownership of land. Images :044-050,188-209,471-479

- Angar Gutin, Modern smallholder farming

- Angar Gutin is a scheme in the category which aims to develop Modern Smallholder Farming. It is located at 1400 m altitude, about 70 km north of Nekempte the capital of Wollega Province, some 400 km west of Addis Ababa.

- Angar Gutin was started in 1971 by Solidarité et Développement, a private German, Belgium and Dutch funded charity agency, associated with the Catholic Church.

- The objective of SED was to achieve integrated rural development with emphasis on human development local leadership and training. The establishment of a rural community was envisaged with 75 % of the settlers engaged in farming and 25 % in rural crafts and cottage industries, in particular:

- Adapted selection and training methods for settlers and staff

- Improved rural techniques, intermediate technologies, labour intensive and capital saving methods

- Agriculture: soil conservation, sound land-use, improved ox traction for farm operations and improved farm practices

- Health care: malaria control; trypanosome control

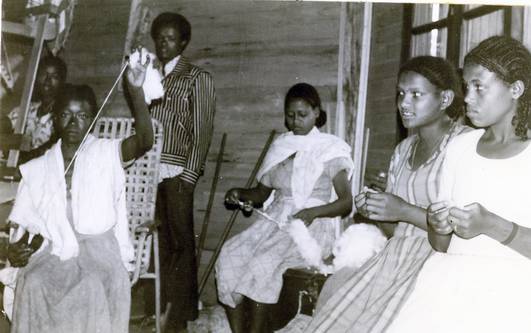

- Rural crafts: brick making, tool making, ox drawn implements; cloth weaving

- Annual target income of $ 500 after deductions for farm inputs and subsistence

- In 1976 there were 590 settler families, but plans existed to extend this to a community of 4 000 families farming 22,000 ha by 1979.

- Settlers were selected from the nearby overcrowded Wollega highlands.

- Development costs amounted to $ 2 000 000.- for the period 1969-1977of which $ 1 500 000 was paid by the donors and $ 5 00 000 was generated by the project, including loan repayments by settlers. Total cost per farm unit was estimated at $ 3700, including a credit to settlers for an amount of $ 1 250.

- Settlers received a 5 ha plot for food crops and a share of 2.5 ha of grazing land and for firewood. The land was cleared by the settler, during which period he would receive a daily allowance for subsistence.

- Each settler received a medium term loan of $ 2,000 for: house construction; one pair of oxen; one improved “Brabant “ plough; one harrow; one yoke and clearing costs.

- Each settler further received a short term loan of $ 260 for subsistence during the first season for: agricultural inputs, seeds, fertilizers and anti trypanosome medicines for oxen. All credit was charged with 7% interest and repayment would after a two-year grace period.

- Infra structural works included: a main feeder road of 60 km; 160 km farm roads; construction of a project center for provision of agricultural services; a cooperative consumer store; ware houses dormitories for trainees; a clinic; schools; water supply and individual wells.

- Extension service: settlers would be twice weekly visited by one of the 24 extension officers

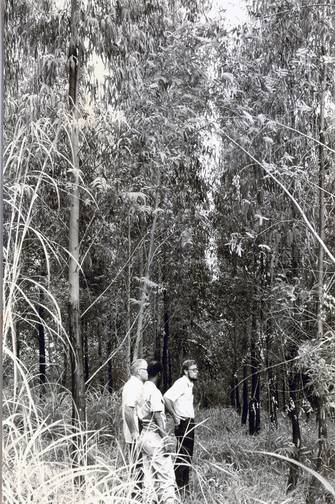

- Trypanosome control by a combination of medications for the livestock and destruction of the tsetse population, through discriminative clearing of tsetse infested bush which is described in detail in the Angar Gutin case study.

- In Angar Gutin the tsetse infection was above 150. In general no livestock is advised when tsetse infections are over 50. In Anger Gutin, in 1976, due to a combination of veterinary and entomological measures the oxen in the project had survived for a period of over 5 years. World-renowned tsetse specialists acknowledged this as an exceptionally positive development and a breakthrough in tsetse control.

- The sales of farm produce and rural handicrafts, including the weaving of cloth, amounted to $ 450 per settler family for the year 1975/1976.

- Farming in Agar Gutin is rain-fed as the annual rainfall is on average 1 400 mm.

- In 1975/76 ha each settler cropped 3.3 ha: 1.8 ha pea beans; 0.5 ha maize 0.4 ha cotton 0.6 ha groundnuts. Net returns for this year were: from crops $ 440, from livestock $ 25 and from handicrafts $ 75; a total of $ 600 per settler family.

- Living expenses during 1975/76 amounted to $ 360 cash and $ 40 for home produce, home consumed.

- Compared with their previous situation settlers found their income and prospects improved. However disturbance by wild animals was worse.

- Problems as seen by settlers: human and animal diseases and transportation facilities to the provincial capital.

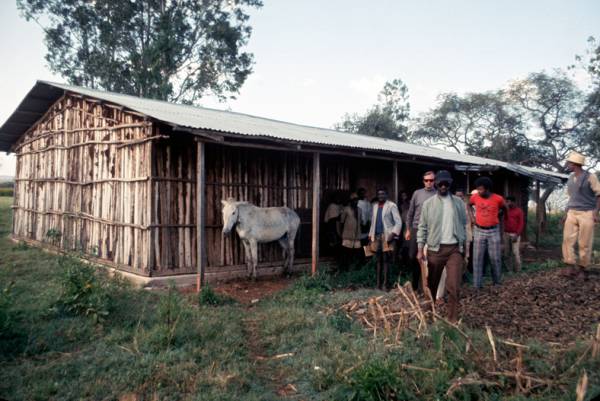

- Problems as seen by the project management: building up managerial capacity; political pressure; improving malaria and trypanosome control; sellingbfarm produce at profitable prices for the settlers and sufficient capital for further development. Images: 001-019,440-446

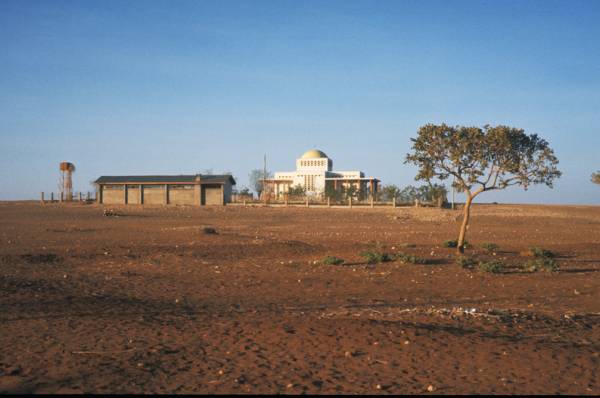

- Amibara, Production oriented large scale mechanized farming

- The aim of the Amibara scheme was production oriented large scale mechanized farming.

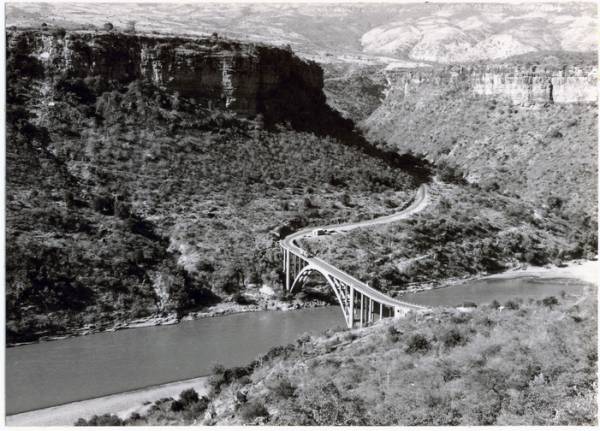

- Amibara is located in the upper middle Awash valley, Haraghe Province on the Addis Ababa-Mille highway, about 280 km north east of Addis Ababa at an altitude of 740 meters

- Amibara was established in 1967 to settle nomadic Afar pastoralists, who had lost their grazing grounds to the Tendeho Cotton Plantation and to introduce irrigated agriculture to the Afar.

- Afar pastoralists had no previous experience with crop production.

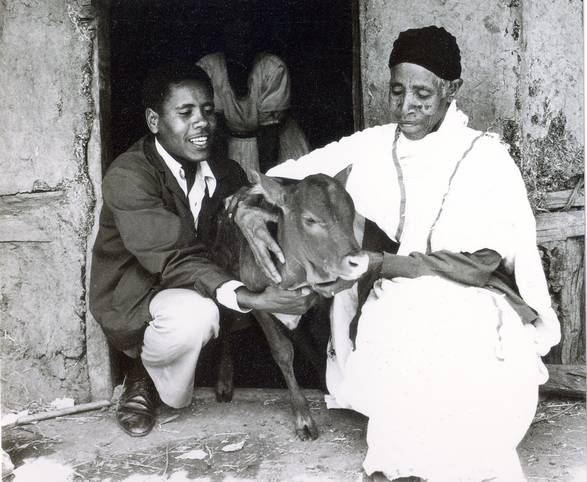

- Before joining the Amibara scheme and before the 1972-1974 drought, the average Afar family owned 245 heads of livestock: 76 cattle; 63 sheep, 62 camels and 43 goats.

- In 1976 there were 409 settler families but a final number of 800 settler families was foreseen.

- Each settler had a share of 2.25 ha in the collective cotton farm, which was actually run by the project , whereby the Afar were engaged as labourer

- The total cost per settler family amounted to $ 3200 including establishment and running of the collective cotton farm.

- The assistance to settlers consisted of a share in the collective mechanized irrigated cotton farm of 2.25 ha, developed for mechanized production: land preparation weeding, irrigation pest and disease control and harvesting.

- Annual credit: This consisted of a monthly food allowance of $ 25 and seasonal farm credit of $ 2 000 per plot, including an amount of $ 425 for hired labour.

- Other services included: roads, ware-houses and a consumer cooperative.

- There would be an extension officer for each 80 settlers, who visited the settlers regularly.

- Marketing of the cotton crop would be collective.

- Amibara had no services for domestic water supply, health care or schooling.

- In spite of the emphasis on mechanization manual labour was still required, which was only for 30% supplied by the settlers, the other 70% of the labour requirements was supplied by highland Ethiopians.

- In 1976 the average settler family had started to rebuilt heir livestock again. At that time most settler herds consisted of an average 48 heads of livestock: Cattle 18, goats 13, sheep 10 and camels 7.

- The Afar settlers actually accepted the money they received from AVA as a compensation for the livestock they had lost due to the damage caused by the Tendaho Cotton Plantation, which started in 1962 and which company by 1976 was farming one third of the area of the Awash flood plain, previously used for grazing by the local Afar tribes. Images-468-470

10. Summary of Conclusions and Recommendations

1. Size of the settler holding

The size of the holding is determined by the desired income level of the settlers

For rain-fed schemes a plot of between 2 to 5 ha plus some grazing land is recommended

For irrigated schemes a plot of 1 ha is recommended

2. Individual or collective farming

In the initial stages collective activities are recommended but after this stage individual farming is recommended as it stimulates the individuals need for responsibilities.

After the initial year of a project, settler selection training and development of local leadership becomes important. Yet pre-selection, apart from age and good health does not seem very essential.

After one or two seasons, with close supervision of the extension staff, a selection may be carried out and those who are capable of working independently may be selected

to run an independent plot, while others not yet capable of working independently are given other tasks. The important issue during the training period is the development of local leadership.

3. Level of support to settlers

The level of support given to settlers depends on the aims of the settlement agency.

As a minimum, settlers are to receive food aid and water supply during the initial stages

Additional support may include:

- Farm inputs, farm tools and plough oxen

- Agricultural extension services

- Basic health services

- Flour mills

- And if relevant, control of malaria and tryposome infections

For development of modern small farmholder farming support is to include:

- Infra structural works, farm roads, service centers, and work shops

- Land clearing and the establishment of irrigation and drainage canals

- Farm credit, marketing and storage facilities

- Consumer supply stores

- Schools and adult literacy programmes

3. General Agricultural Issues

Considering both the experiences and the needs of the Ethiopian farmers it is recommended to establish mixed farming systems, including crop and horticultural crops, animal husbandry and forestry plantations for fire wood supply.

To establish the link between farming and applied agricultural research

To implement strict soil conservation measures

To aim to achieve optimal levels of mechanization, including improved oxen traction and land preparation by tractor

National price policies should be adjusted to encourage settlers and increase their income.

5. Costs and returns from settlement schemes in Ethiopia

Proper record keeping is strongly recommended, as in 1976 no financial data were available for the majority of the settlement schemes included in the survey.

Cost and returns per settler unit for the six case studies

| Name of scheme | Type of scheme | Investment per holding $ | Est. return per holding /year $ |

| Gato | Self help | $ 125 | $160 |

| Chano | Self help | $ 150 | $300 |

| Dimtu | Self help improved | $ 1 350 | $300 |

| Abella | Modern small holder | $ 2 000 | $500 |

| Angar Gutin | Modern small holder | $ 1 500 | $550 |

| Amibara | Mechanized farming | $ 3 200 | $ 1 400 |

6. Staff

Staff selected to supervise settlement schemes should have at least a junior agricultural college level education. In addition, they should be given short courses on settlement aspects, including development of leadership and agricultural issues.

Staff should receive adequate salaries and lodging arrangements.

7. National Settlement Inventory

It is recommended that a continuing national settlement inventory is undertaken to allow rapid adjustment of policies and arrangements when needed

8. National Settlement Policy

It is recommended to establish a national policy to guide settlement in Ethiopia.

ANNEX I

1. The Konso:

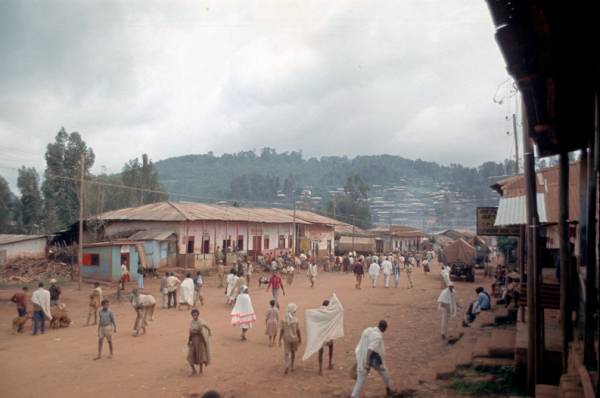

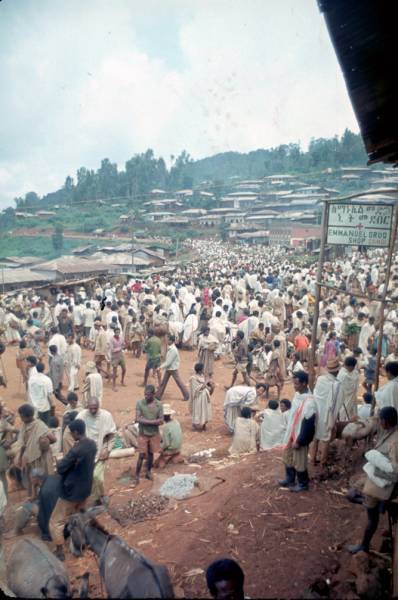

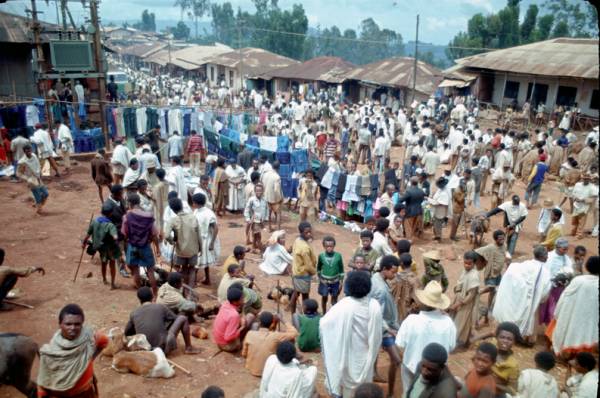

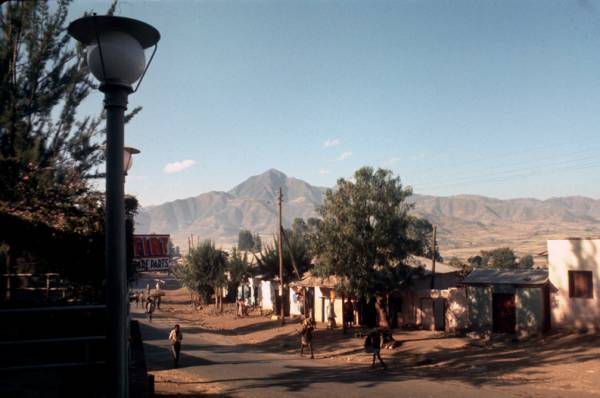

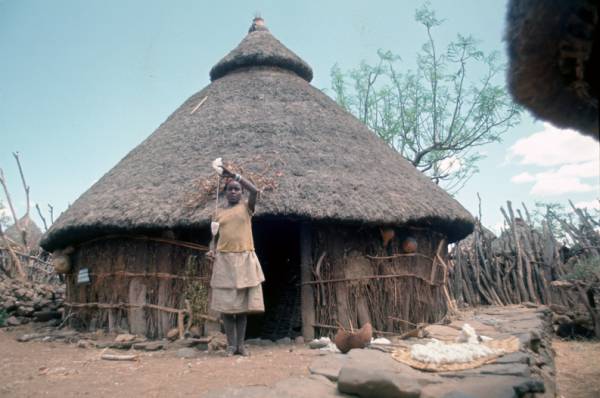

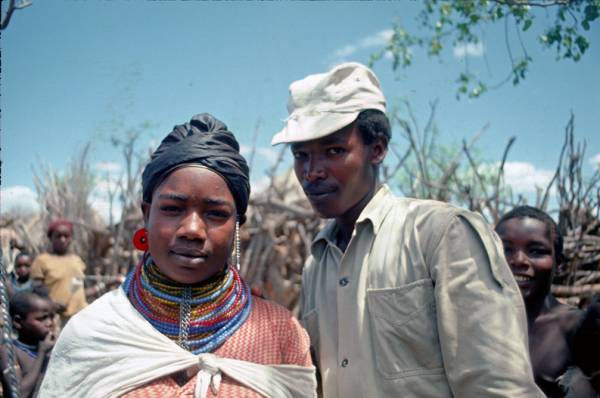

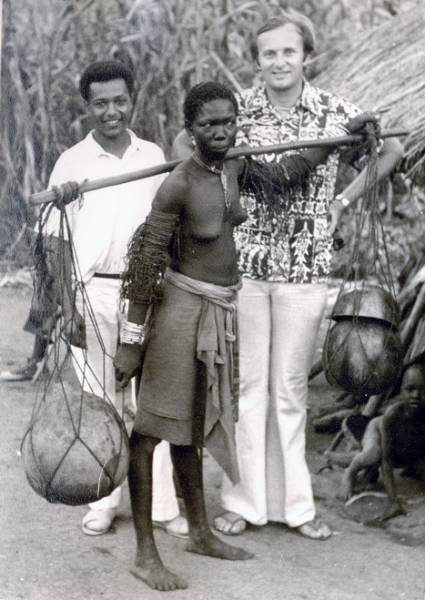

During my travels in South Ethiopia I also visited the Konso area. Konso town is located near the Sagan River in southwestern Ethiopia about 100 km south of Arba Minch in Gema Gofu province at 1650 m altitude. The reason to visit Konso was that it had also received food aid and that land suitable for settlement schemes was reported in the neighborhood of Konso.

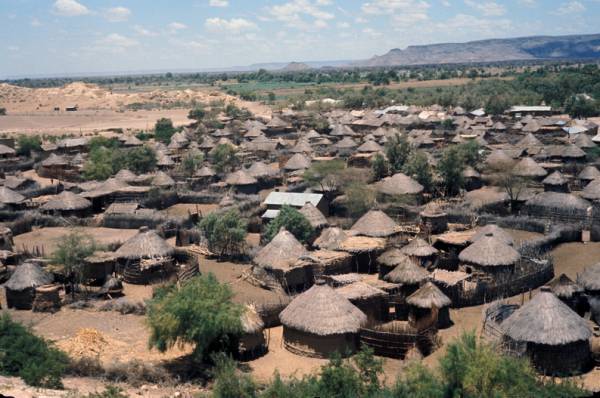

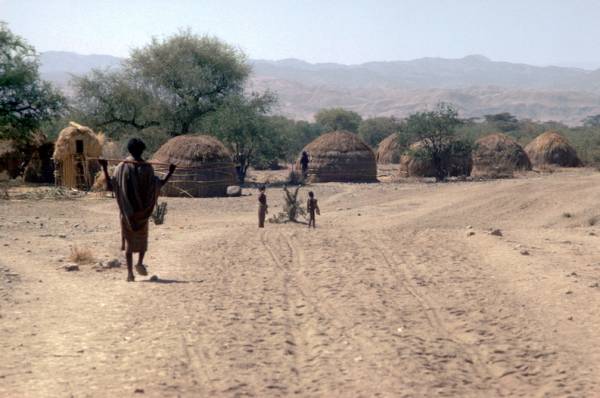

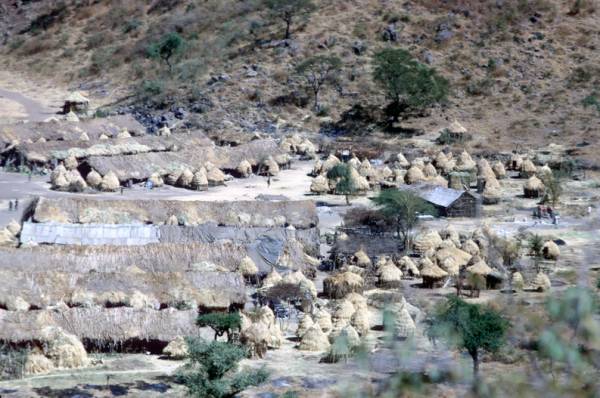

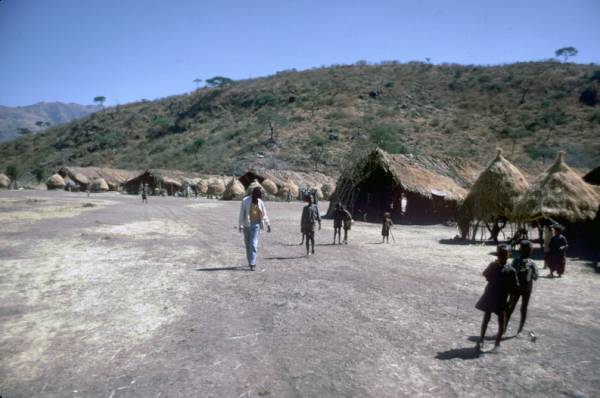

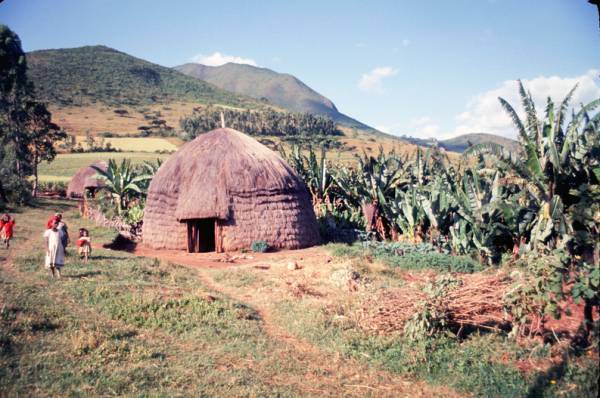

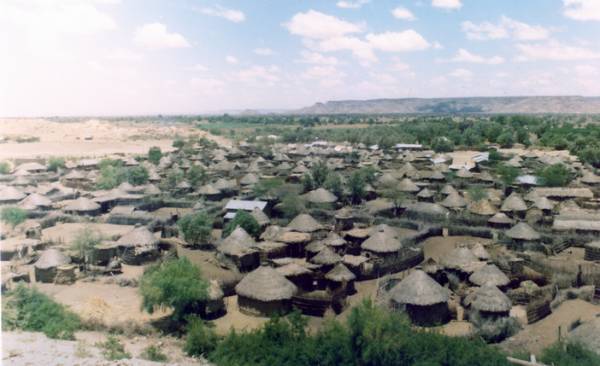

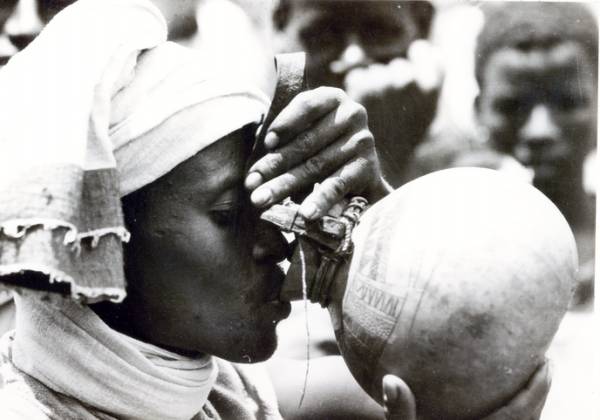

I found Konso a very interesting place to visit. In 1976 the Konso population consisted of some 3 000 inhabitants. Konso was a large town with traditional huts. The town was governed by a council of elders and in 1976 was still surrounded by an ancient wall, constructed from large stone blocks. The Konso are Cushitic speaking people of mixed Caucasoid and Negroid ancestry.

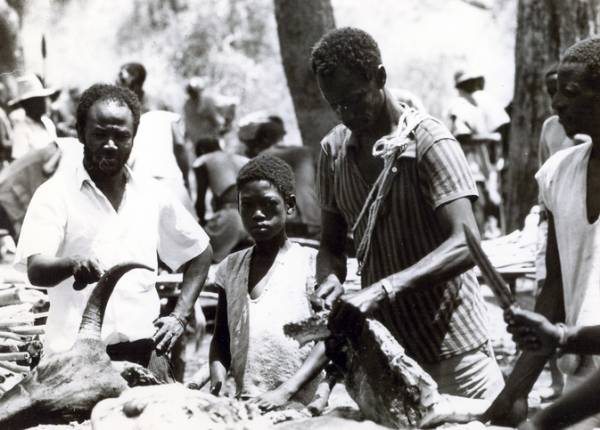

The farm fields of the Konso are situated on terraces surrounded by walls of stone on very swampy land and are beautifully graded. Konso crop production is a very intensive and terraces are rainfed. Crops include: sorghum, millets and maize as food crops and cotton and coffee as cash crops. Livestock included cattle, sheep and goats, which are all stable kept and fed. Animal dung is collected and transported manually to the farm fields for fertilization. The milk forms an important part of the diet of the Konso. Bee keeping is also an important industry and I still remember having carried a large container of honey with me to Addis Ababa. Another activity is spinning and weaving traditional homespun cloth, using self grown cotton.

The Konso people are a colorful people. They make interesting wooden statues of their ancestors called wagas, which represent the warrior, his wives and his slain enemies, or large game such as lions. Groups of these wagas can be found in many places outside the walled town.

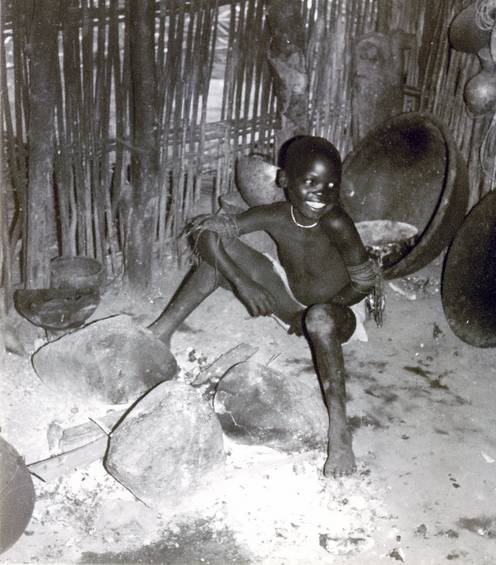

The Konso are the only Ethiopian people who still make and use stone stools for working on their farm fields. Curiously, all stone tools are made by Konso women.

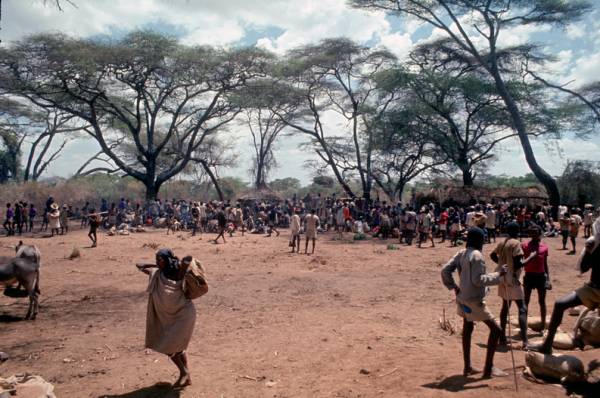

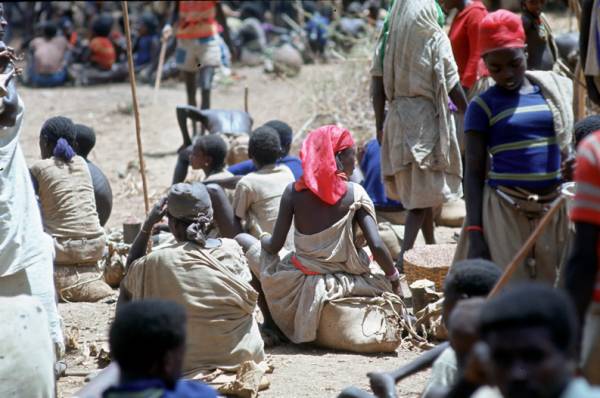

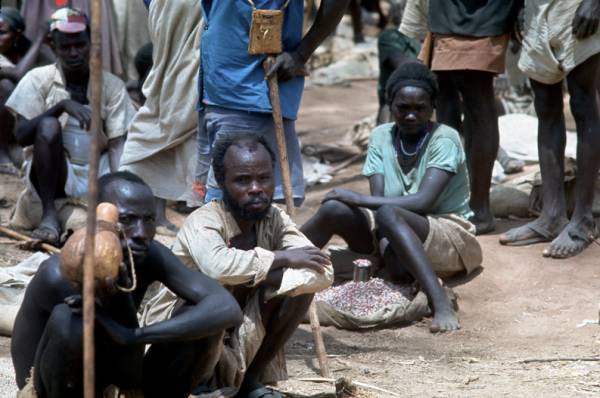

I also enjoyed their local market just outside the walled town.

The Konso have similar age group systems as most Cushitic groups, such as the Oromo in Ethiopia and the Massai in Kenya. It is a generation grading system, which divides society into nine different kinship groups or clans and whereby each clan is divided into nine age groups, which are each headed by a priest. These groups also arrange the inheritance of traditional property. Each group of workers forms a kinship group as for example the crafts-men and the warriors.

Images =133-134,239-280,304

2. Living in Addis Ababa during the 1974-1979 Revolution

Living in Addis Ababa, during the Revolution, was a complex experience.

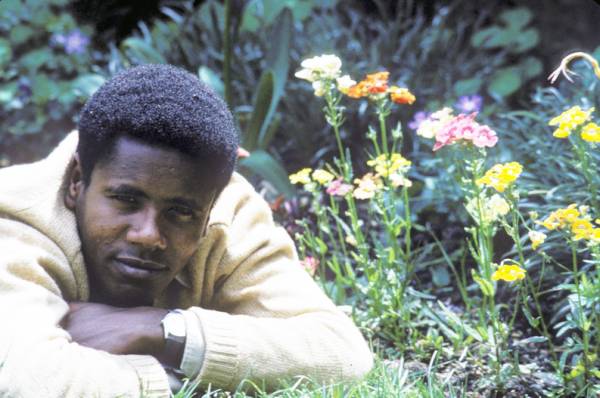

Ethiopians, regardless their tribal background, are very kind and friendly people.

The climate of Addis Ababa, at an altitude of 2500 m was very pleasant. Midday temperatures were up to 30 C, but due to the relative dry mountain climate, one never felt hot. After 5 pm near dusk, the temperature rapidly fell to nearly 0 C and most evenings, Asfaw, my houseboy, lighted the open wood fire in the living room. Asfaw’s marriage with a girl from his village was also a special day for me.

During all the years of my stay in Ethiopia, there was a curfew between 10 pm and 6 am, which was extended from 6 pm till 6 am during the 1977 -1978 war with Somali, when many Russian and Cuban soldiers and officials were staying in Addis Ababa to help Ethiopia. This was mainly an effort to reduce the killing of Russians and Cubans government advisors helping the Government with fighting the Somali, by parties who did not agree with the Government Marxist policies. At night one often heard shooting and during some periods, when driving in the morning to the office, one saw on the street the dead bodies of people killed during the past night.

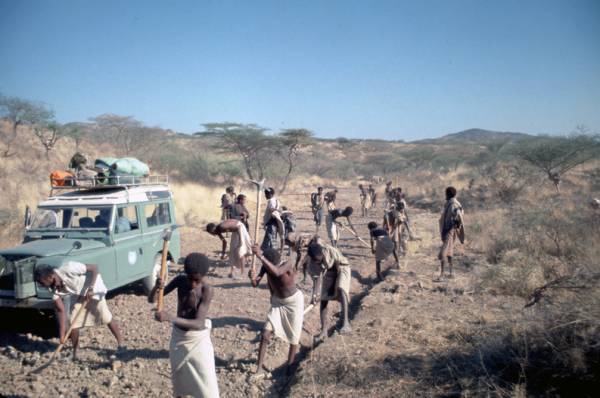

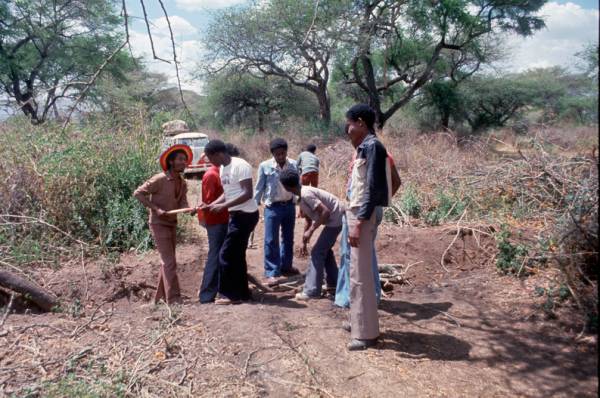

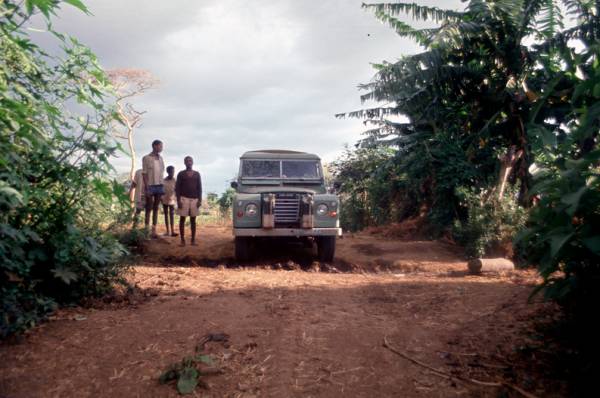

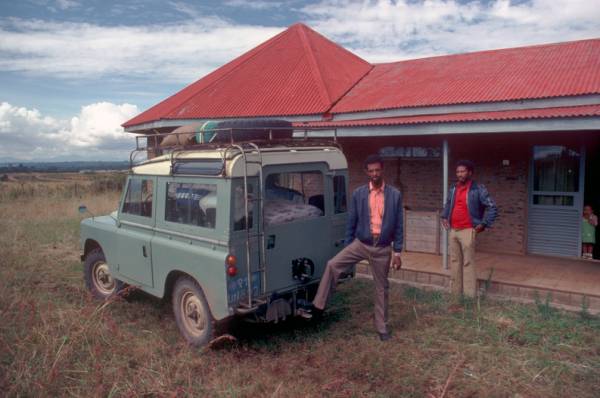

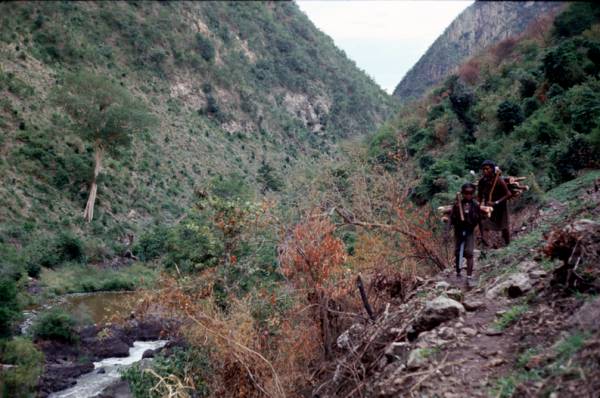

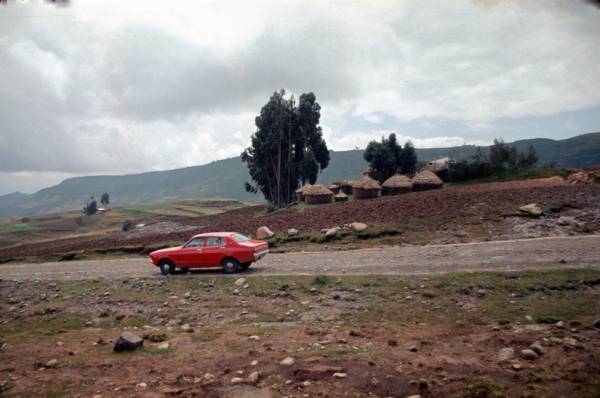

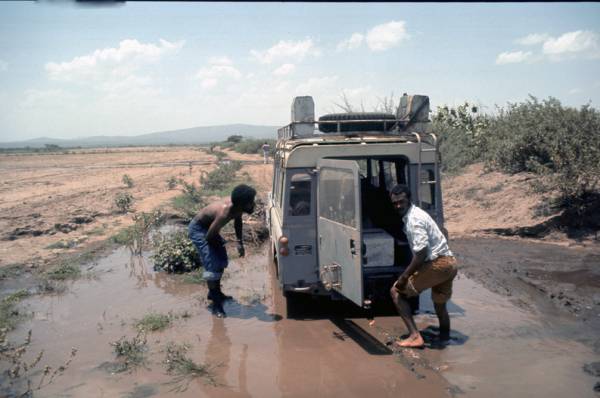

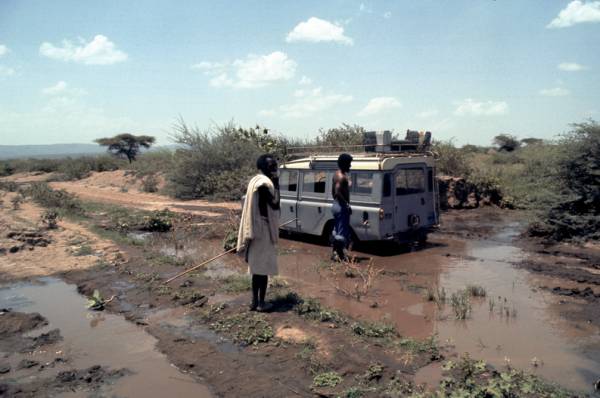

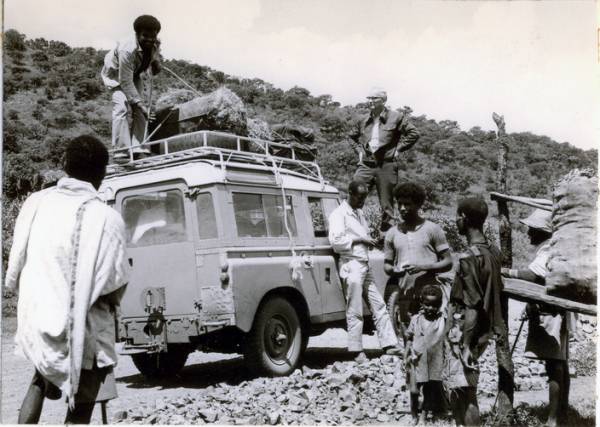

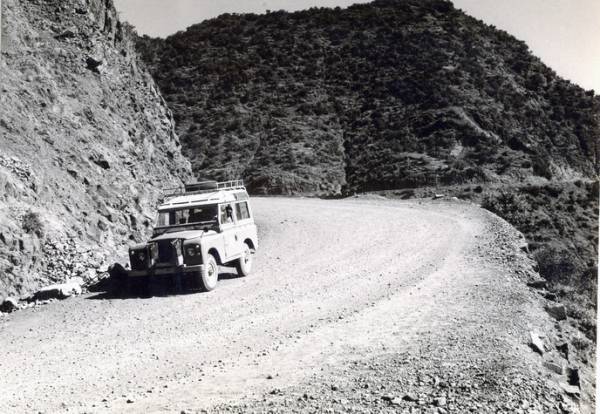

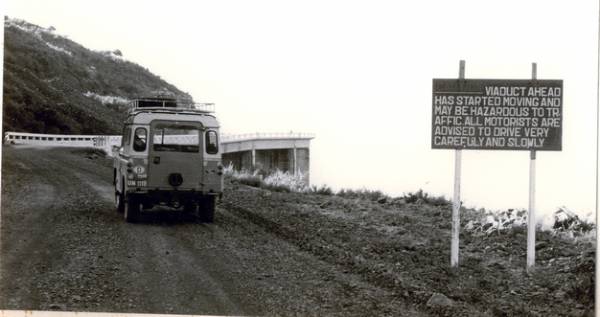

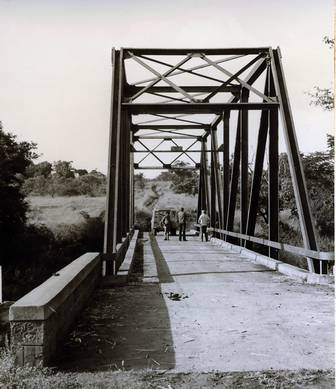

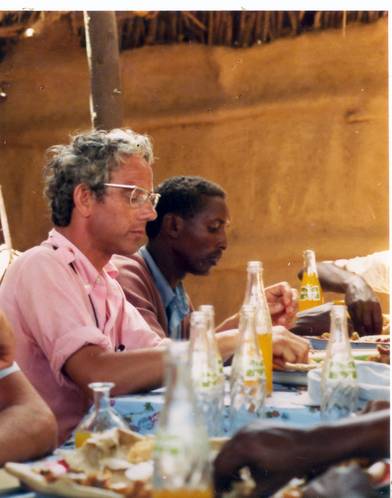

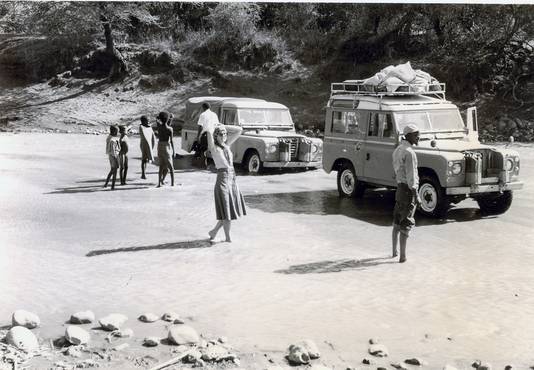

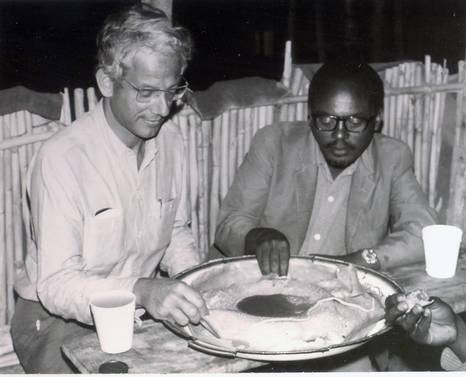

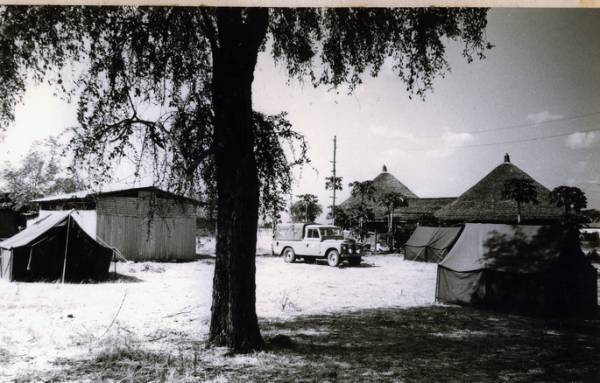

Petrol was rationed, which restricted traveling within the extended Addis Ababa area, as some friends lived more than 20 km from my house. Outside Addis Ababa no petrol was available. For our field trips we obtained a special allowance and carried our own petrol, from 800 to 1000 liter in 200 liter drums, depending on the travel route. To ship the fuel an additional land rover pickup to carry the fuel, joined our convoy, which always consisted of three to four heavily loaded land rovers. We carried food, water and camping equipment.

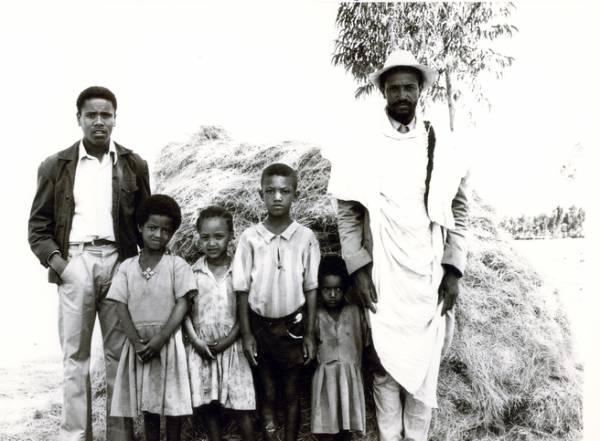

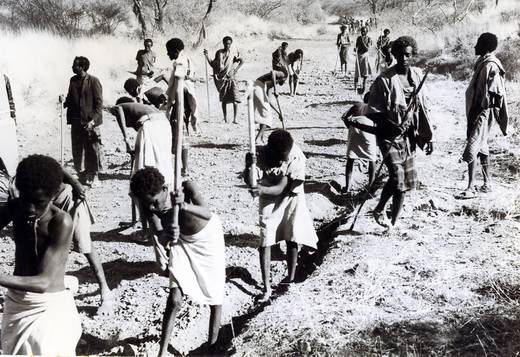

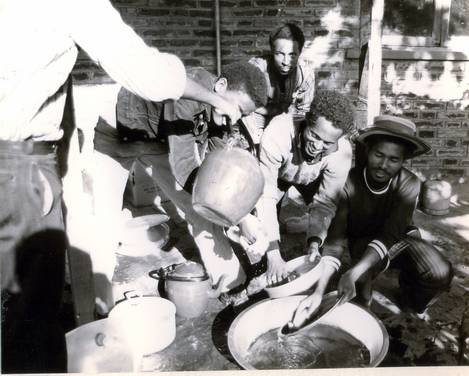

About half the time during the first two years of my stay in Ethiopia I was traveling to visit the locations of the nearly 100 settlement schemes and future sites for schemes. My team consisted of one or two college graduates and six enumerators, who were all university students, so called Zematch, who were ordered by the regime to work for one year with the peasants, similar as in Marxist Russia, China or Cuba. The student members of my team were selected to assist our survey, due to their excellent knowledge of English. Most of their classmates were sent to remote primitive villages far from Addis Ababa for periods of a year or longer. Our enumerators had only trips of two to three weeks after which they returned to Addis Ababa.

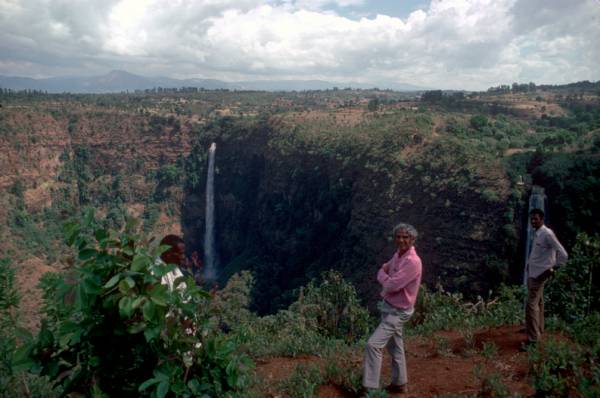

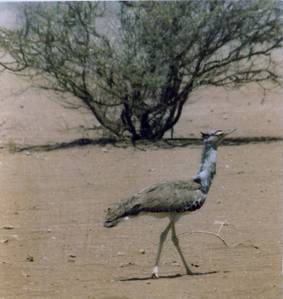

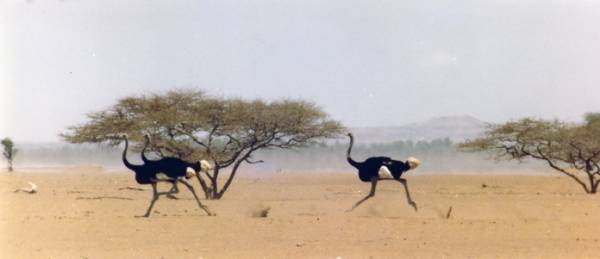

The mood during our field work was pleasant. The days were long, the roads were in poor condition, but the landscape was very beautiful, particularly along the edge of the Rift Valley with mountain views and beautiful lakes, some covered by thousands of rose coloured flamingos. Most interviews and visits to settlement farms were interesting and it appeared that many settlers were full of a new spirit and wanted to work hard to improve the future of their families. All were happy that the old Haile Selassie regime had collapsed and many of its corrupt officials eliminated.

Most of the days we camped and cooked our own food, as there were no hotels in the areas where we traveled. Occasionally we stayed in the guest house of a settlement scheme.

Essential food supply was available during most of my stay. During some periods wheat flower was not available and bread had to be was made from a mixture of maize and rye flower. Cooking oil was also occasionally difficult to obtain, while European foodstuff, such as cheese and jams, were seldom available. One had to make do with locally available food. Fortunately Asfaw sometimes went on an expedition to his home village, 100 km north of Addis Ababa to buy a bag of 50kg wheat, which was milled nearby our house. Asfaw always baked delicious bread for me. The local Ethiopian wine was excellent and easily available and I also enjoyed the very delicious types of local honey.

My house in Addis Ababa was a bungalow in a government compound with eight units. As the pictures show, it was a comfortable residence. Gardening was an attractive hobby. The well drained grey vertisols, the ample sunshine and the absence of most pests and disease made working in the garden a pleasure. I cultivated roses, dahlias, gerberas, tomatoes and sweet peppers and succeeded in making Dutch tulips produce flowers in February 1979. First I stored the bulbs in the refrigerator for two months. Hereafter, I planted the tulip bulbs, which I gave an additional three hours of light from a simple desk lamp every evening. The tulips bloomed as in Holland.

Another hobby was playing baroque music with a group of friends: there were violin, cello, piano and cembalo players, while I played either the flute or recorder. Several times a year we gave concerts for friends in the house of one of us and we also joined the British Anglican church when they organized a concert. Furthermore I did much reading, about Ethiopia and many other subjects.

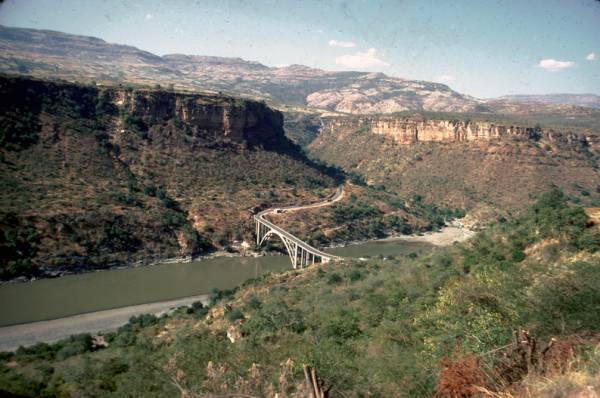

During my last two years in Ethiopia I joined a walking club and on many Sundays we climbed one of the nearby mountains, visiting old Coptic churches or enjoying beautiful mountain landscapes. Sometimes I did some horse riding with Anne, a British nurse in the nice countryside around Addis Ababa. During the last year of my stay restrictions to travel outside the town were somewhat reduced and I made an interesting trip to the delta of the Blue Nile and visited the house of Asfaw, my houseboy, which was situated a 100 km north of Addis Ababa.

Images 332-369

Annex III

References

1. Monographs and photo books

| 1 | Atkins , Harry R. | 1975 | Ethiopia Land of Enchantment |

| 2 | Englebert , Victor | 1970 | The World of an Ethiopian Boy,

Harcourt New York |

| 3 | Ethiopian Tourist Org. | 1975 | Handicrafts of Ethiopia |

| 4 | Forsberg, Malcom | 1975 | In famine he shall redeem thee,

Sudan Interior Mission |

| 5 | Gérard, Bernard | 1973 | Ethiopia, Delroisse, Paris |

| 6 | Gerster ,Georg | 1970 | Churches in Rock, Early Christian Art in Ethiopia, Phaidon, New York. |

| 7 | Kapuscinski Ryszard | 1978 | The Emperor, Haile Selassie – Ras Tafari, Knipscheer Haarlem |

| 8 | Kon. Inst v de Tropen | 1975 | Ethiopia |

| 9 | Last G & Pankhurst R | 1972 | A history of Ethiopia in pictures, Oxford U.P. |

| 10 | Markakis J. &

Nega Ayele |

1978 | Class and Revolution in Ethiopia, Russell Press, Nottingham |

| 11 | Moorehead, Alan | 1962 | The Blue Nile , Harper& Row , New York:

Part Four: The British in Ethiopia |

| 12 | Levine Donald N. | 1972 | Wax & Gold Tradition & Innovation in Ethiopian Culture, University of Chicago Press |

| 13 | Pankhurst , Richard | 1965 | Travelers in Ethiopia, Oxford University Press |

| 14 | Ullendorff, Edward | 1973 | The Ethiopians , An introduction to country and people, Oxford University Press |

| 15 | Westphal, Egbert | 1975 | Agricultural Systems in Ethiopia,

Pudoc, Wageningen, The Netherlands |

| 16 | Mehari Gebre Medhin & Bo Vahlquist | 1976 | Famine in Ethiopia –A brief review American Journal of Clinical Nutrition Sept 1976 |

| 17 | Tsegay Wolde-Georgis | 2008 | El Nino and Drought : Early Warning in Ethiopia |

2. Reports by Charles van Santen

| 1. | Six Case studies of Rural Settlement Schemes in Ethiopia | 1978 | Case Studies

UNDP/FAO Settlement Project, Addis Ababa |

| 2. | Rural Settlement Schemes in Ethiopia | 1979 | Main Report

UNDP/FAO Settlement Project, Addis Ababa |

| 3. | Ethiopia, | 1979 | End of Assignment Report

UNDP/FAO Settlement Project, Addis Ababa |

| 4. | WADU 1971-1976 | 1979 | A case study for the impact of WFP Food Assistance, in Ethiopia |

| 5. | Rural Settlement Schemes | 1988 | Dissertation submitted to Pacific Western University |

3. Overview material for photo gallery

| 1. Slides 331 general slides & 29 personal slides | 360 |

| 2. Negative films | 20 |

ANGER GUTIN

Settlement Scheme

Wollega province

A Case Study

of

Development of modern smallholder farming

Solidarité et Développement