2.3.1 Ur

Ur, of the Chaldees, the birth place of Abraham 1900 BC, was one of the most important Sumerian towns between 3000- 500 BC. It is located near Nasseria, about 350 Km SW of Baghdad. In the Sumerian period it was located on the Euphrates, which now has moved about 10 km to the east of Ur.

Ur was excavated by Sir Leonard Woolley 1922-1934:

One of his famous finds was the royal cemetery with the grave of King Abargi, who was buried with 74 of his court staff and many gold, silver and lapus lazuli artifacts including harps, carts with draft bulls and other objects.

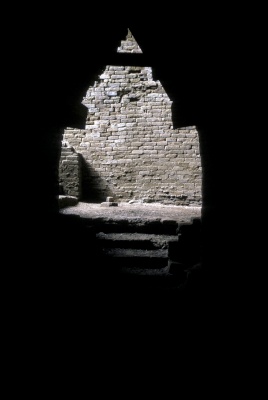

The most famous period of Ur was the third dynasty with King Ur Nammu and his sons and descendants: 2200- 2000BC.Ur Nammu and his sons built the ziggurat and most of the important temples in Ur and in other towns of his empire, among others in Uruk, Larsa, and Babylon The present ruins of ziggurat are the remains of the restoration by Nebucadnezzar and his son Nabonius in the 600- 500 BC period.

Also important was the Larsa period from 2000- 1800 BC. The excavations also obtained found much information from this period and the following period when Hammurabi was king of Babylon and also conquered Ur. The excavated streets of the Larsa period give a picture of street life in old Sumer.

References: Excavations at Ur. 1954 Sir Leonard Woolley

Additional notes by Noah Kramer Ur of the Chaldees, ancient cities of Mesopotamia.

Its ruins are approximately midway between the modern city of Baghdād, Iraq, and the head of the Persian Gulf, south of the Euphrates River, on the edge of the Al Najarah Desert. The site of Ur is known today as Tall al Muqayyar, Iraq. In antiquity the Euphrates River flowed near the city walls. Controlling this outlet to the sea, Ur was favorably located for the development of commerce and for attaining political dominance.

Ur was the principal center of worship of the Sumerian moon god Nanna and of his Babylonian equivalent Sin. The massive ziggurat of this deity, one of the best preserved in Iraq, stands about 21 m (about 70 ft) above the desert. The biblical name, Ur of the Chaldees, refers to the Chaldeans, who settled in the area about 900 BC. The Book of Genesis (see 11:27-32) describes Ur as the starting point of the migration westward to Palestine of the family of Abraham about 1900 BC.

Ur was one of the first village settlements founded (circa 4000 BC) by the so-called Ubaidian inhabitants of Sumer. Before 2800 BC, Ur became one of the most prosperous Sumerian city-states. According to ancient records, Ur had three dynasties of rulers who, at various times, extended their control over all of Sumer. The founder of the 1st Dynasty of Ur was the conqueror and temple builder Mesanepada (reigned about 2670 BC) The earliest Mesopotamian ruler described in extant contemporary documents. His son Aanepadda (2650 BC) built the temple of the goddess Ninhursag, which was excavated in modern times at Tell al-Obeid, about 8 km (about 5 mi) northeast of the site of Ur. Of the 2nd Dynasty of Ur little is known.

Ur-Nammu (reigned 2113-2095 BC), the first king of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur, who revived the empire of Sumer and Akkad, won control of the outlet to the sea about 2100 BC and made Ur the wealthiest city in Mesopotamia. His reign marked the beginning of the so-called renaissance of Sumerian art and literature at Ur. Ur-Nammu and his son and successor Shulgi (reigned 2095-2047 BC) built the ziggurat of Nanna (about 2100 BC) and magnificent temples at Ur and in other Mesopotamian cities. The descendants of Ur-Nammu continued in power for more than a century, or until shortly before 2000 BC, when the Elamites captured Ibbi-Sin, king of Ur 2029-2004 BC and destroyed the city.

Rebuilt shortly thereafter, Ur became part of the kingdom of Isin, later of the kingdom of Larsa, and finally was incorporated into Babylonia. During the period when Babylonia was ruled by the Kassites, Ur remained an important religious center. It was a provincial capital with hereditary governors during the period of Assyrian rule in Babylonia.

After the Chaldean dynasty was established in Babylonia, King Nebuchadnezzar II initiated a new period of building activity at Ur. The last Babylonian king, Nabonidus (reigned 556-539 BC), who appointed his eldest daughter high priestess at Ur, embellished the temples and entirely remodeled the ziggurat of Nanna, making it rival even the temple of Marduk at Babylon. After Babylonia came under the control of Persia, Ur began to decline. By the 4th century BC, the city was practically forgotten, possibly as a result of a shift in the course of the Euphrates River.

The ruins of Ur were found and first excavated (1854-55) by the British consul J. E. Taylor, who partly uncovered the ziggurat of Nanna. The British Museum commenced (1918-19) excavations here and at neighboring Tell al-Obeid under the direction of the British archaeologists Reginald C. Thompson and H. R. H. Hall. These excavations were continued from 1922 to 1934 by a joint expedition of the British Museum and the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania under the direction of the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley.

In addition to excavating the ziggurat completely, the expedition unearthed the entire temple area at Ur and parts of the residential and commercial quarters of the city. The most spectacular discovery was that of the Royal Cemetery, dating from about 2600 BC and containing art treasures of gold, silver, bronze, and precious stones. The findings left little doubt that the deaths of the king and queen of Ur were followed by the voluntary death of their courtiers and personal attendants and of the court soldiers and musicians. Within the city itself thousands of cuneiform tablets were discovered, comprising administrative and literary documents dating from about 2700 to the 400 BC. The deepest levels of the city contained traces of a flood, alleged to be the deluge of Sumerian, Babylonian, and Hebrew legend. All scientific evidence, however, indicates that it was merely a local flood.

Reference: Edmund I. Gordon & Samuel Noah Kramer

2.3.1 Uruk

Uruk, Erech from the bible was one of the main cities from Sumer. Uruk was already an important town in the Jamdat Nasr period 3500 BC and during the proto literate period. The archeologists assume that writing was invented in Uruk. Examples of series of picto grams have been found in the oldest civilization layers of Uruk, which over time gradually changed into abstract cuneiform letters. Very early libraries of picto grams already contained lists of stocks of goods and persons, with name, functions, responsibilities and contracts.

I visited Uruk several times, during my stay in Iraq, in the period 1966-1969 to meet Prof Lenzen and his team of archeologists. Professor Lenzen had been excavating in Uruk since 1927 when he was a team member under Prof. Heinrich. Later, during the 1950s he became the director of the German Uruk expedition. When I met him in the period 1966-1969 he continued his work in Uruk after his retirement. Prof Lenzen mentioned that they had gradually worked backwards in time during the excavations, started with the youngest layers in 1927 and now in 1967-1968 finally reaching the proto literate period from 3500-3000 BC. Pits were dug under the Eanna and Kallub ziggurats from the 2200-2000 BC periods to search for older temples and palaces. The team found many large palaces and temples and a large quantity of primitive clay tablets showing the development from pictograms to cuneiform script. One particular temple which was measured during one of my visits measured 90 by 40 m. According to Prof. Lenzen most temples and buildings were of similar size. The temples of the Proto literate period 3000-3500BC were decorated with large columns, with diameters of up to 3 meter. These columns were covered with geometric mosaics which were made from baked and painted terra –cotta cones with a flat end. Tests showed that dominant colors of the painted cones were red, black and light yellow or whitish. It must have been quiet impressive to see the front of temple of some 30 meters wide, with these colonnades all covered with colorful mosaics. A few years earlier, in 1960, Prof Lenzen’s team had found nearby one of the temples a large collection of golden, silver and lapis lazuli artifacts in an early grave of a king of the proto literate period, indicating that already 500 to 700 years before the famous grave of Queen Shub –Ad from Ur the custom existed to bury royal persons with many artifacts and with a number of their servants. Prof Lenzen gave us passionate explanations about the marvelous temples and ziggurats of the Proto Literate Period 3000-3500BC, which he had excavated. During another visit he showed us an ancient underground archive. This was located under the Eanna Ziggurat and contained large collections of unbaked soft clay tablets with Sumerian cuneiform writings. Immediately after the discovery of the underground archive Prof Lenzen took an unbaked clay tablet out of the archive to study it in the open air, in the hot and dry Iraqi climate. Unfortunately after a few minutes the tablet crumbled in his hand and became dust. The remaining hundreds of clay tablets were immediately baked and preserved. After the entire collection of clay tablets was removed and safeguarded Prof Lenzen investigated the archive and found that the bottom of the cellar was covered with porous stone slabs, containing hundreds of very small holes. Under the slabs he found a rapid moving underground water stream. Due to the friction of the water stream against the stone slab with the holes, water evaporated and therewith created an artificial more humid climate sufficient to preserve the unbaked clay tablets in good condition. The Sumerians were thus familiar with the concept of climate control.

The first question Prof Lenzen asked himself why so much trouble to keep the tablets humid. However as soon as a few tablets were translated it was found out that all the clay tablets in this archive were land deeds. Obviously these land deeds needed to be adjusted each time after land was transferred to a new owner through inheritance or sales. This explained the need for the tablets to remain unbaked and thus to be alterable. This condition allowed the scribe to alter the deed with his clay pen made from a sharp piece of reed and add the name of the new land owner. Clay tablets with religious text were always baked as there was no need to change these. The Sumerians assumed that the text of these tablets was given to man by the Gods.

During an other occasion Prof Lenzen mentioned that according to his calculations during the early second millennium Uruk had already over one million inhabitants, on its total area of nearly 600 hectares. Rome, only reached the one million inhabitants mark during the 1st century AD. According to the Gilgamesh Epic one third of the area of Uruk was used for temples, one third residential houses and one third for gardens. Thus Prof Lenzen suggested that within the town boundaries and in the near surroundings an intensive garden agriculture was established to feed the large number of inhabitants. A branch of the Euphrates was used for irrigation. Some food stuff and most material needed for such a large town were imported from the colonies which had been established by the Uruk state in many locations in Mesopotamia, Iran and the Mediterranean plateaus. Such material included building material, wood, gold, silver, copper, lapus lazuli.

These materials were all used in Uruk but were not locally available. During the second millennium Uruk was the largest and most important town of the world. After this period Uruk remained a large town and important religious centre till around 654 AD when it was destroyed by an Arab army. The Sassanian population of that time fled and left the site waste, till the arrival of the European explorers in the nineteenth century.

References

Main reference: Roux Georges: 1964 Ancient Iraq – World Publishing Company

The cradle of civilization by Samuel Noah Kramer 1967

The Greatness that was Babylon. H.W.F. Saggs 1962

Every day life in Babylonia & Assyria. H.W.F. Saggs 1965

The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient. Henri Frankfort 1954

The Sumerians. Samuel Noah Kramer, 1963

Digging up the past. Sir Leonard Woolley, 1930

Excavations at Ur. Sir Leornard Woolley, 1954

Babylon, James G. Macqueen, 1964

Atlas of Mesopotamia, M.A. Beek. 1962

Encarta Reference Library Microsoft 2003

Mesopotamia, the Invention of the City, Gwendolyn Leick. 2001

Atlas of Archeology Collins Past Worlds. Times Books 2003

Mesopotamia and the Ancient East. Cultural Atlas. Michael Roaf. 2003

In addition personal information from Prof Lenzen