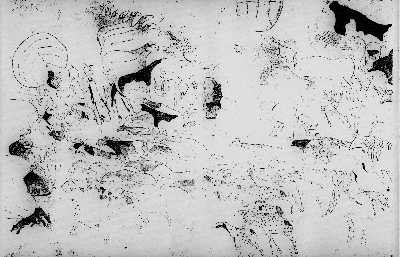

Rock paintings by Neolithic pastoralists

Living between 4000 BC and 2000 BC at

The Tassili n’Ajjer Plateau, Sahara, South Algeria

Photo gallery and Introduction

My 1972 visit and follow up studies

The interpretation of an agriculturalist

Charles Emile van Santen

Agricultural Economist & Agriculturalist

Bogor, Indonesia October 2007

Contents

1. INTRODUCTION

2. THE TASSILI ROCK PAINTINGS

2.1. Conditions in the Sahara and the Tassili plateau during the Neolithic period

2.2. Description of the Tassili rock paintings

2.3. Comparing prehistoric Tassili images of village life with those of 20th century

traditional West African pastoralists: The interpretation of an agriculturalist

2.4. A hypothesis about the motivation of the prehistoric pastoralists to create the

rock paintings.

3. BACKGROUND NOTES

3.1. My 1972 travel through the Sahara and the Tassili n’Ajjer Plateau

3.2. Developments in other parts of the World between 4000- 2000 BC

3.3. Hypotheses about motivations for the creation of the Tassili rock paintings by

Lhote, Le Quellec, McKenna & von Daniken

3.4. Holls’ analysis method of prehistoric composite rock paintings:

The Sahara Rock Art: Archeology of Tassilian Iconography 2004.

4.REFERENCES

5.PHOTO GALLERY:

1. Maps : TAS001-003

2. Rock paintings:

2.1.Images by others : TAS004-047

2.2.Images by Charles : CVSALG001-027

3. Sahara images:

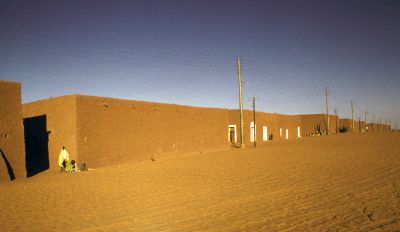

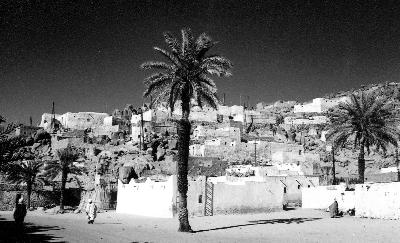

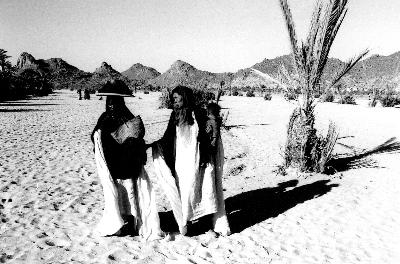

3.1 Desert towns and oasis: CVSALG028-076

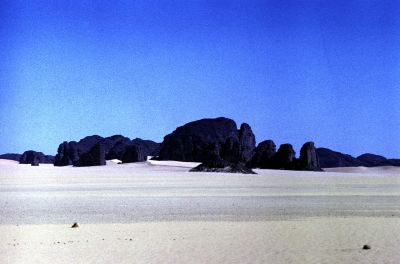

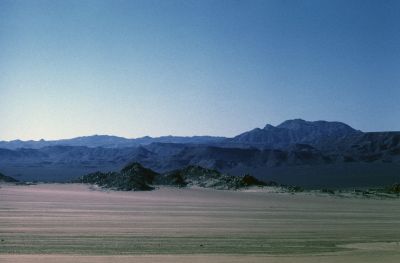

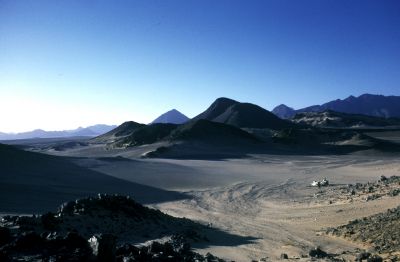

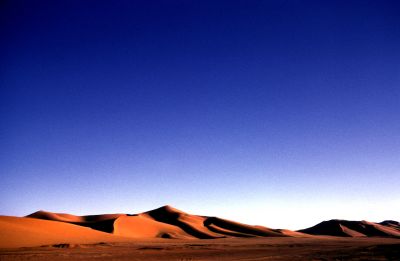

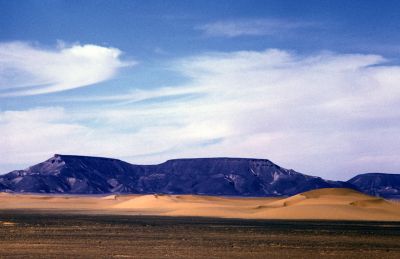

3.2 Desert landscapes : CVSALG077-109

3.3 Tassili landscapes : CVSALG110-171

1. INTRODUCTION

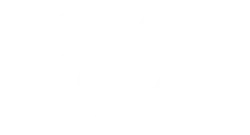

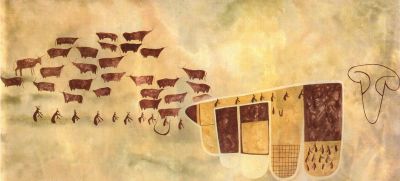

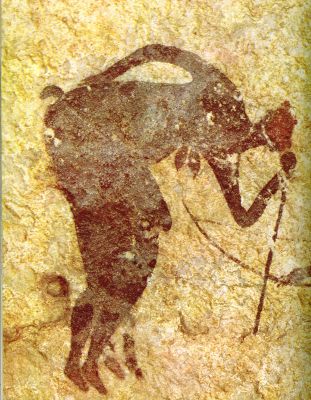

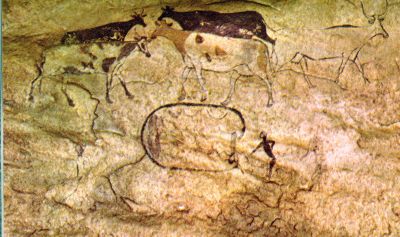

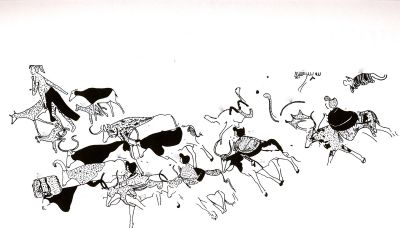

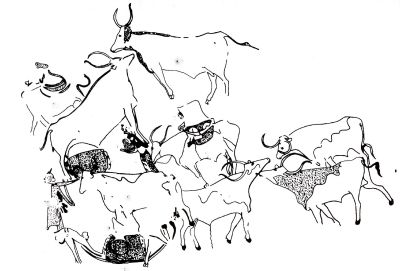

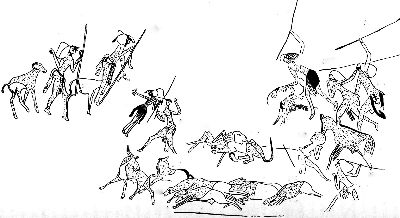

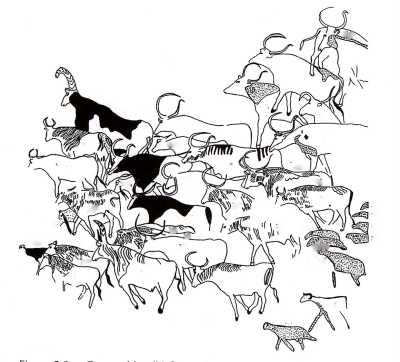

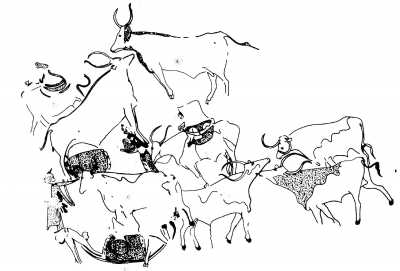

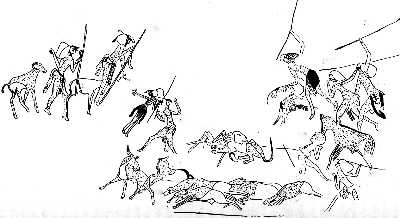

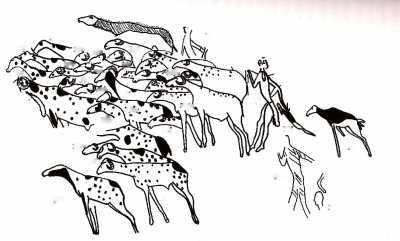

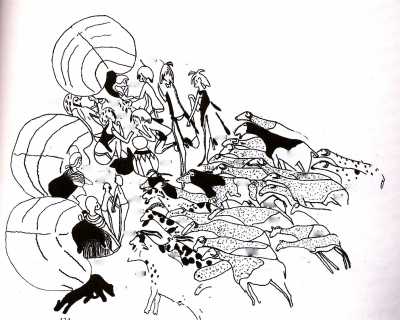

In early 1970, I read a fascinating book written in 1958 by Henri Lhote, a French Sahara specialist: The search for the Tassili rock paintings – A la découverte des Fresques du Tassili. In his book Lhote describes how he and a team of artists copied over a thousand of large prehistoric rock paintings and identified some further 20 000 paintings on the walls of caves and semi caves of the Tassili n’Ajjer plateau, Central Sahara, South Algeria, during fifteen annual expeditions between 1955-1970. The following three images from his book show the high quality of the Tassili rock paintings: tas004-006, showing two images of cattle herds and one of women praying to a divinity.

Studying the images of prehistoric rock paintings in Lhote’s book, it struck me that many of the prehistoric village life scenes appeared rather similar to those of traditional rural societies I observed daily in West Africa while conducting socio- economic surveys as an agriculturalist. I therefore decided to visit the Tassili n’ Ajjer plateau to see the prehistoric village scenes depicted in the rock paintings. I further liked the opportunity to travel again through the desert which had fascinated me since my travels through deserts in Tunisia 1961, Iraq 1966-1969 and Iran 1967.

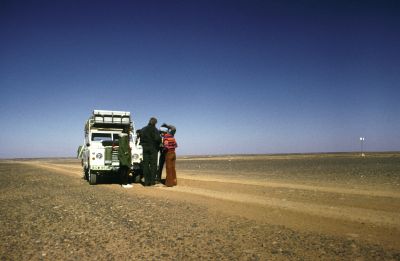

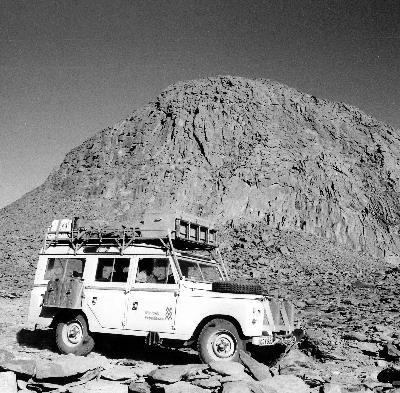

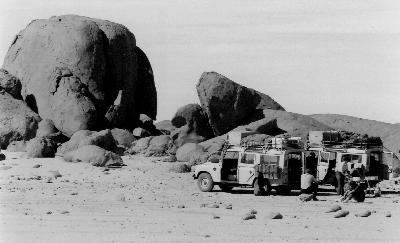

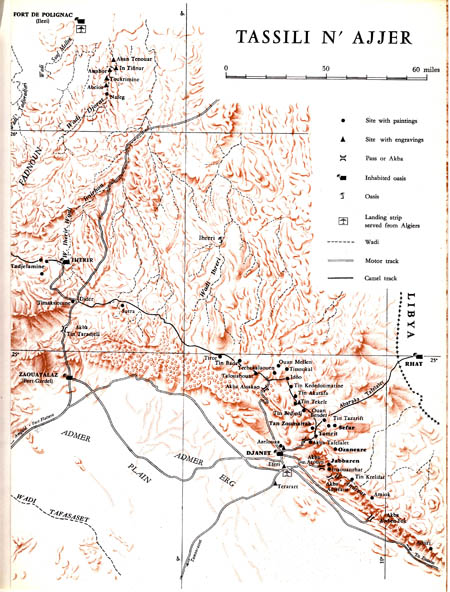

Following this in January 1972, I joined a group of people with similar interests through Minitrek. This organization made available to us two skilled desert drivers and two Land Rover four wheel drive vehicles especially reinforced. In 1972 this was needed as the Sahara tracks at that time were still in poor condition. We started our trip in Algiers, which trip would cover about 4 500 km by car through the Sahara and about 100 km trekking on foot on the Tassili plateau, to visit the prehistoric rock paintings. A detailed account of my 1972 trip is presented in: Background Notes 3.1: My 1972 travel through the Sahara and the Tassili plateau. Route maps are shown in tas001-003.

After completion of my trip in 1972 I continued collecting information on the prehistoric pastoralists’ Tassili rock paintings. Reviewing early 2007 newly published publications and other information, available since 1972, I decided to write up my findings and compliment these with a photo gallery of the prehistoric rock paintings and my 1972 travel through the Sahara.

2. THE TASSILI ROCK PAINTINGS

2.1 Conditions in the Sahara and the Tassili plateau: Neolithic period 4000 BC-2000 BC.

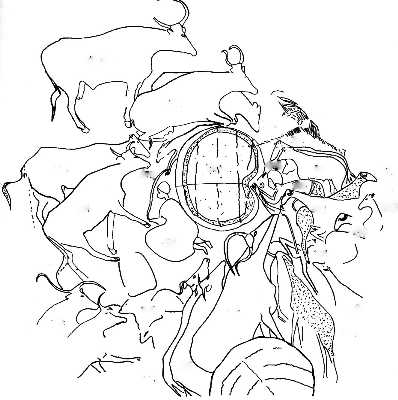

Rainfall in the Sahara during the Neolithic period from 4000 BC to 2000 BC was higher as today as the abundance of wildlife in that period shows. The many wildlife images depicted among the Tassili rock paintings and engravings are a proof of this and include elephants, giraffes, lions, ostriches, gazelle, Oryx, mountain sheep, rhinoceros, wild oxen, apes and wart hogs.

We may assume that many parts of the Sahara during this period were covered with savanna vegetation: scattered trees, covered with grass during the rainy season, comparable to the present savanna vegetation in the Sahel, the climatic zone south of the Sahara. Neolithic camp sites with finds of flint stone arrow points and stone tumuli or burial sites on the Hoggar plateau and adjacent areas in the Sahara, confirm human habitation. C14 radio-carbon analysis of campfires remains, including bones of larger wild life, indicate dates of human habitation of the Hoggar plateau between 4000-2000 BC.

Present day transhumant pastoralists in the Sahel zone, during the rainy season, move their herds from one suitable grazing spot to another in the low lands, using seasonal rivers and creeks to water their herds. At the beginning of each dry season, when grazing opportunities are running out, these herdsmen move their herds to areas near rivers where still sufficient grazing and water is available for their herds.

Similarly we may assume that during the rainy season, the prehistoric transhumant pastoralists grazed their herds at the Hoggar plateau at an elevation of 1 000 meter, which is proven by the many Neolithic campsites found in that area. At the beginning of the dry season the Neolithic pastoralists moved their herds up to the Tassili N Ajjer plateau, at an elevation of 1500 meters, where during this season still sufficient grass and water would have been available for their herds. The many rock paintings and samples of Neolithic household goods found in the Tassili plateau caves confirm human habitation in this area. Household goods included among others: pots, stone knives, axe points and grinding stones. C14 radio-carbon analysis of campfire remains and pollen from the Tassili plateau caves, indicate that this area was also inhabited during the period 4000 -2000 BC.

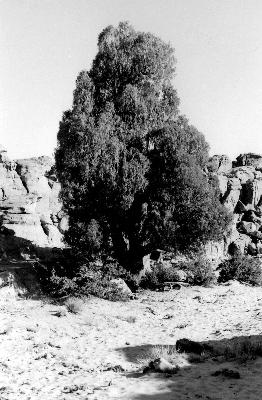

The Tassili n’ Ajjer plateau, the location of the rock paintings, is a large sand stone plateau in the Sahara in South Algeria about 700 km long by 100 km wide, rising above the surrounding Hoggar massif. During the Neolithic period the Tassili plateau rainfall was higher as today, as is proven by the remnants of oak-, cypress-, olive-, alder- and lime trees which still are found to day in Tassili.

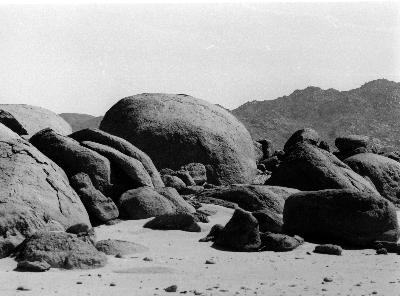

Today water is rarely present on the Tassili plateau, remaining in deep shaded rocky cracks, locally called gueltas. The only perennial river in the central Sahara is in the Iherir area. In the past long before the Neolithic population lived on the plateau wind erosion and the arid climate created rock formations resembling ruins or stone forests. In other areas of Tassili fluvial action over the millennia formed narrow deep gorges in these flat plateaus, which resulted in a unique network of steep-sided valleys with caves interspersed with some flat areas.

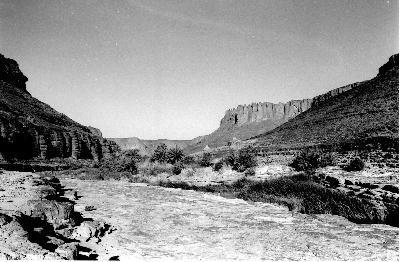

The prehistoric rock paintings are mainly found in the caves of these steep sided valleys. Images of the Tassili landscape are shown in cvsalg110-171

2.2 Description of the Tassili rock paintings

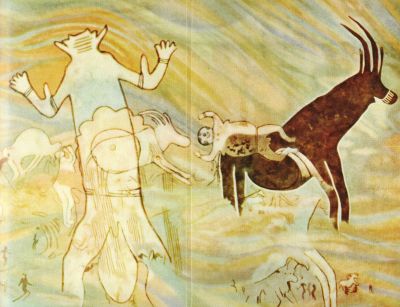

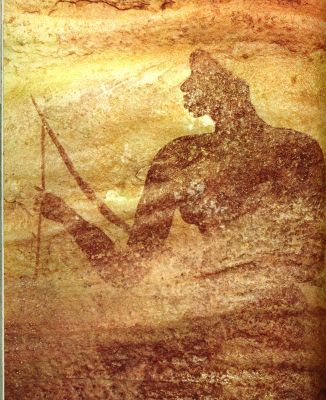

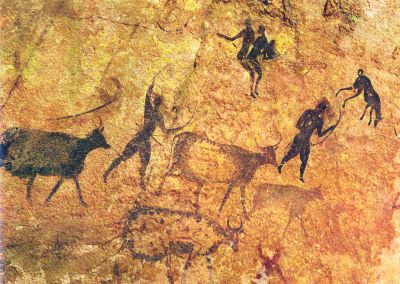

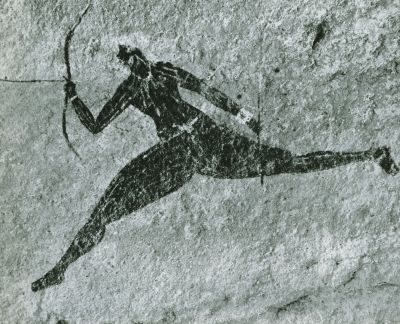

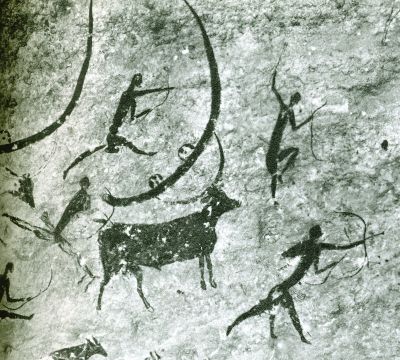

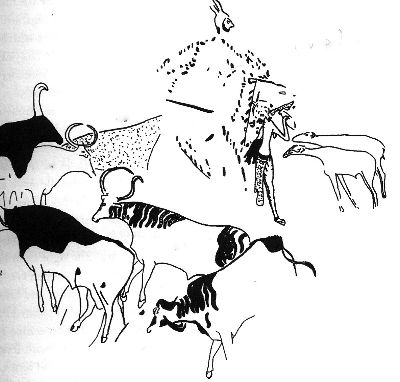

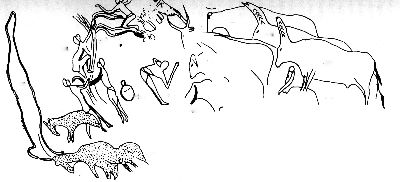

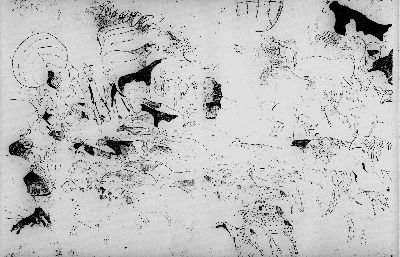

The Tassili prehistoric rock paintings show a wide range of styles from the naturalistic to the near abstract. Some of the paintings are really beautiful with a high artistic value. As an introduction a selection of details from 21 rock paintings is shown here: tas007-029. These photos were taken by the professional photographer Jean-Dominique Lajoux in 1961. Lajouxs’ images in my opinion give a better impression of the rock paintings as compared with the copies made by the artists of the Lhote team between 1955 and 1970.

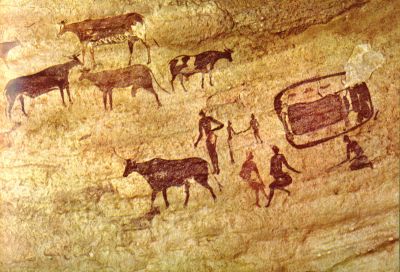

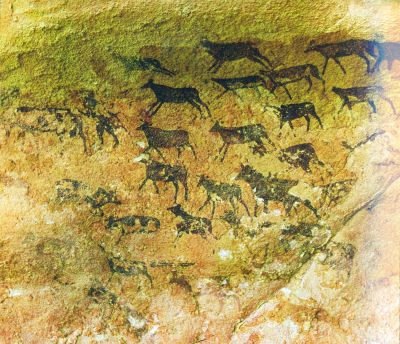

An overview of the Tassili paintings show following subjects:

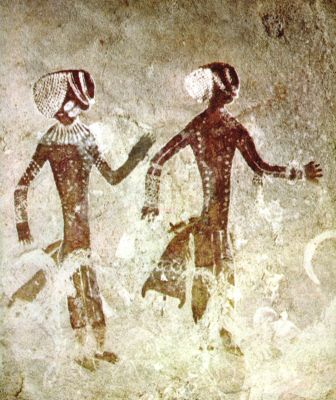

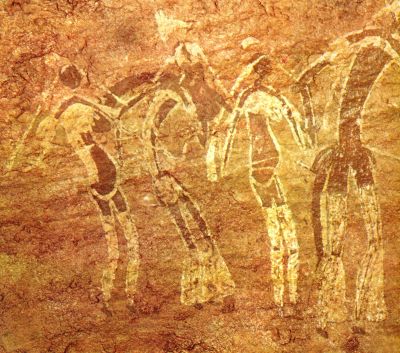

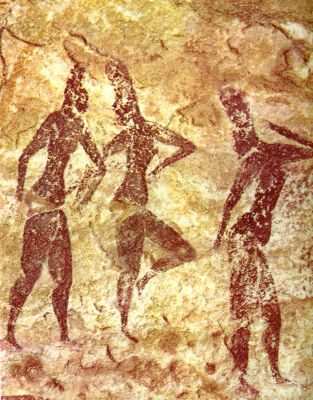

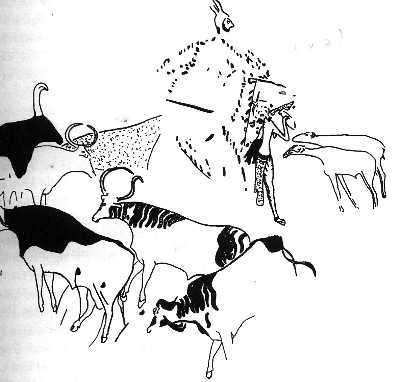

- Humans, predominantly with Negroid features, while some locations show humans with Caucasian features. The main clothing styles appear to be rather similar to present day traditional rural West African styles of clothing: long flowering dresses and head cloth for women and men and loin cloth for young men, while dancers depicted, used also body paint designs similar to the present West African style. A few images show Egyptian style short clothing.

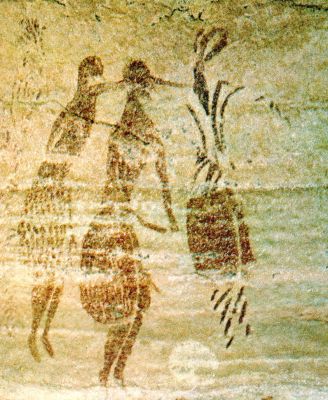

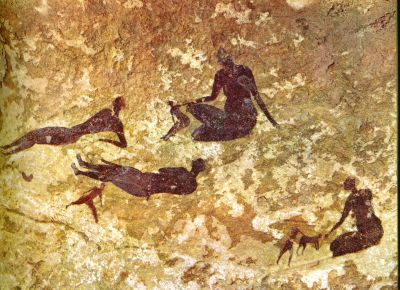

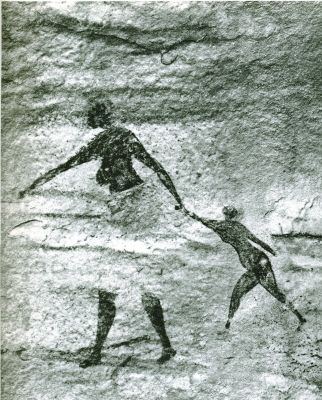

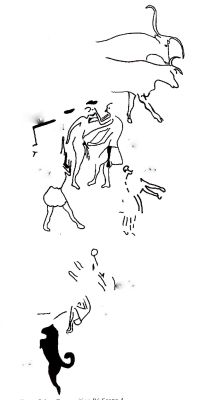

- Village life scenes: Village gatherings in which people meet in front of their huts to chat; pregnant women deliver their babies; parents playing with their children inside and outside their huts; people watering their cattle, sheep and goats; people dancing; women harvesting grains; young men with spears, hunting a lion which had taken one of their sheep; young men picking wild fruits from a tree; ceremonies and rituals, some of an erotic nature, probably related to fertility or procreation rites.

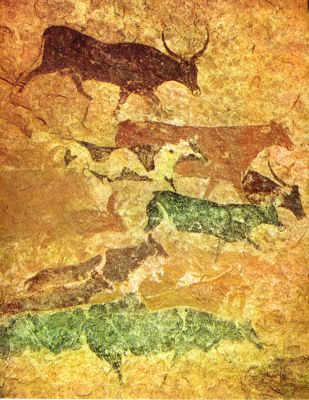

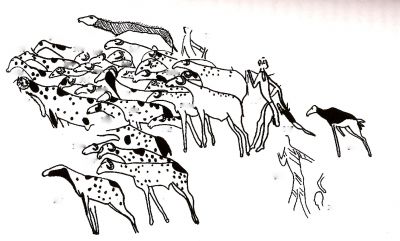

- Livestock: Cows with several different types of horns, udders, skin designs and colors; sheep, goats and dogs, also with variations in skin design and types.

- Wildlife: Elephants, giraffes, wild mountain sheep, lions, ostriches, gazelle, Oryx, rhinoceros, wild oxen, African buffalo, apes, wart hogs, crocodiles and fishes.

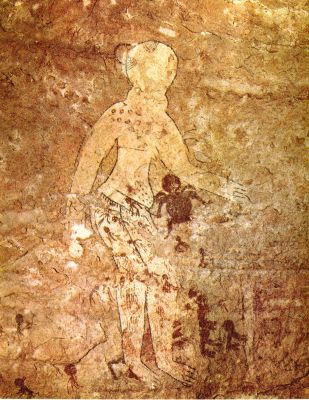

- Divinities: Some images show large strange types of divinity figures, with worshippers

around. An example is shown in tas006

The average size of the rock paintings

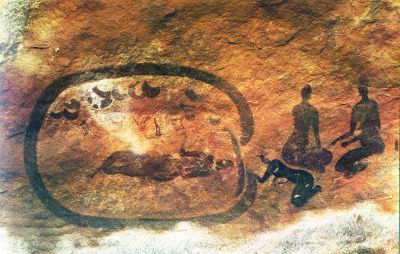

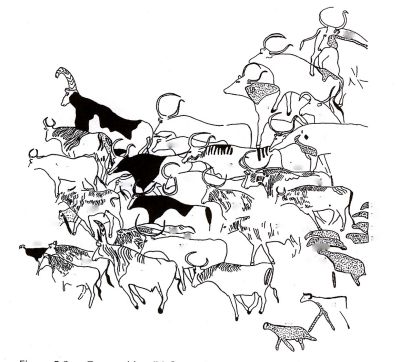

The average size of the composite rock paintings is large and measures typically 120- to 300 cm wide and 400- to 600 cm high. For example the composite rock painting with livestock scenes in the Iherir area, which will be analyzed in section 3.4, measures 300 cm wide by 250 cm high and depicts 120 humans, 280 domestic animals, 47 wild animals and 66 objects such as drinking vessels, hut frames and mats.

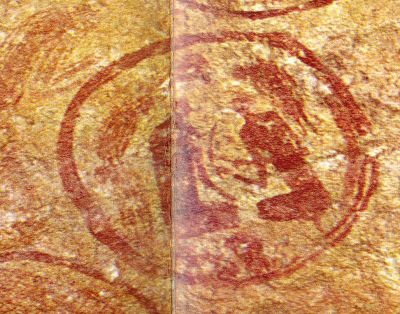

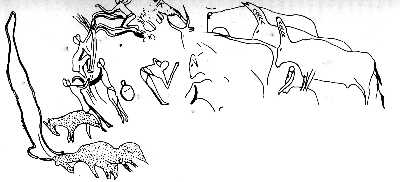

Palimpsest: Overlapping of images.

Most paintings show several layers of images in different styles, which overlapping of images is called a palimpsest. This overlapping of two or more layers of images in different styles shows that several different cultural groups and generations of people have used the same area for their paintings, whereby each group painted images in their own style, disregarding images from previous groups. Examples are images: tas013Lajoux and cvsalg016

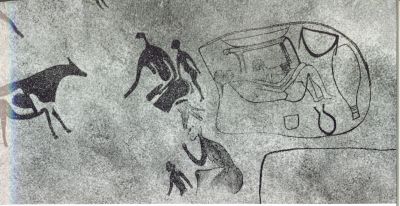

Composite pictures illustrating village life

A major characteristic of these paintings is their composite nature. Each painting describes a specific village life story divided over several components or scenes, whereby each component or scene shows a different aspect of the same story comparable to a “strip” story. To illustrate this point, I refer to the detailed analysis of one Tassili composite rock painting from the Iherir area, recently published in a monograph entitled: Sahara Rock Art, 2004, Archeology of Tassilian Pastoralists Iconography by Holl, A.F.C.

Holl, a professional archeologist, anthropologist and university professor specialized in West African anthropology, developed a useful pictorial analysis method for interpretation of composite rock paintings. Holl applied his analysis method to a large composite rock painting depicting many cattle and humans, located in the Dr. Khen shelter in Iheren, in the Central Tassili, north of the Wadi Tadjelamine bend, some thirty kilometers west of Iherir. The structure of this painting was identified as a narrative, representing an allegory and morality play with a complex story line, which was divided into distinct compositions and organized into different tableaux and individual scenes. The analysis of this Tassili rock painting shows that it describes village life of traditional African pastoralists, supporting my assumption on this issue. For an example of Holls’ pictorial analysis method see images tas031-047. A short note explaining his pictorial analysis method is given in section 3.4

Source of the paint material or pigments, range of colors and painting technologies

The prehistoric artists obtained their pigment or coloring material from ochreous schists. Schists are rocks whose minerals have aligned themselves in one direction in response to deformation stresses. The result of this is that these rocks split in parallel layers. Each layer of these rocks had a different position and was therefore exposed for a different period to sunshine. This resulted in different ochre pigment colors for different layers, ranging from dark to light depending on the number of hours of sunshine received. Ochre is a mineral composed of clay and hydrated ferric oxide and is used as a pigment varying from dark brown to light yellow. In the case of the Tassili n’Ajjer ochre schists, the range of colors is very wide: The most protected schists gave a very dark ochre color, almost the color of dark chocolate, while colors of other layers ranged from brick red, light red, and yellow shades up to a greenish hue.

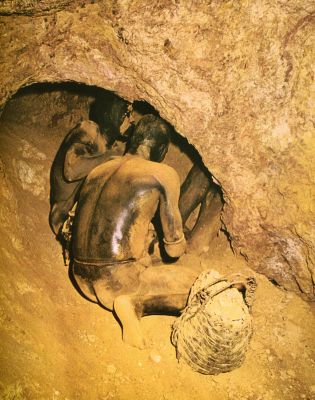

A white color was obtained from locally available kaolin. The result of the availability on the Tassili plateau of this wide range of ochre shades is that the palette of colors used in the Tassili rock is much richer as compared with the palette of red ochre, kaolin white and oxide of manganese found in prehistoric rock paintings in other locations. Image tas030 taken in the Nubian mountains in West Sudan shows the collection of ochre from caves, in a similar way as during the Neolithic period at the Tassili plateau. Some Nubian tribes, from West Sudan, used ochre as pigment or coloring material base for body painting till recently.(Riefensthal)

The artists grounded these pieces of ochre schist to powder in a stone grinder, which is confirmed by the many examples of prehistoric grinding stones found in the Tassili caves. After the colored schist powder was obtained it was mixed with a media.

Most likely this was based on casein, a milk product, as cattle were ample available to the prehistoric Tassili people. Another possibility for a media could have been acacia gum, taken from the many acacia trees growing in the area.

2.3. Comparing prehistoric Tassili images of village life with those of 20th Century traditional West African pastoralists: An agriculturalist’s interpretation

As mentioned earlier, familiar with present day village life of traditional rural West African societies through my work as a socio economic agriculturalist, I was able to compare 20th century village life scenes of traditional rural West African societies with those depicted in the prehistoric Tassili rock paintings and observed many similarities between the two groups. I also refer to my web site: www.cvsanten.net, : Liberia section, which contain some of my photographs of village life of traditional West African societies. It is my intention to upload in the near future additional photographs of traditional village life scenes from other West African countries.

In the following list similarities in village life between the prehistoric pastoralists and modern day West African traditional pastoralists are shown:

- Herds with cattle, sheep and goats;

- People watering and tendering their livestock;

- People making camp sites: unloading or loading household goods on cattle, constructing huts made from straw mats on wooden frames;

- Village people meeting in front of their huts; eating; chatting; admiring a newly born baby or a newly born calf or lamb; drinking from large earthenware containers; taking care of dogs as pets; participating in grain harvesting; hunting; picking fruits; dancing; erotic activities; rituals and praying to divinities.

The above list of characteristics, relevant for both prehistoric and 20th century traditional rural groups, leads to the following description of pastoralist societies:

- During the wet season transhumant pastoralists move their herds between areas with good grazing and watering in the savanna, with scattered trees and wet season grass vegetation. During the dry season the herds are moved to higher elevated locations or near to rivers where still sufficient grass for grazing and water is available.

- The pastoralist economy is based on cattle, sheep and goats, with a diet based on milk and in some tribes with blood, supplemented with grains and fruits collected or exchanged with farmers.

- Rituals relate to live circles of men and livestock within the seasonal changes. These include practical subjects such as watering, grazing and taking care of livestock; collecting wild fruits and grains; & hunting; and cultural subjects such as praying to divinities and conducting fertility rituals.

- Huts made from straw mats, easily foldable and movable between seasons and village camp sites.

- Clothing is made from wool and skins: loin cloth for men and long dresses for men and women; use of earthenware drinking vessels; the keeping of dogs as pets.

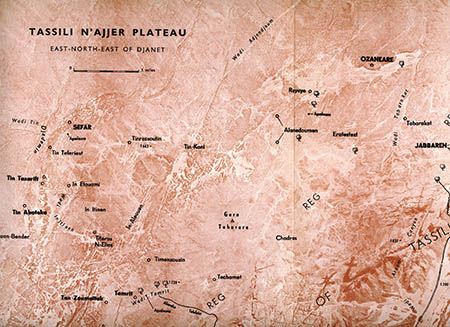

NB. My personal study of prehistoric rock paintings is based on visits to two major Tassili sites: Sefar and Jabbaran and four minor sites: Tamrit, Tin Aboteka, Tin Tazarift and Tin Itinen. See Map tas002 Tassili plateau & tas003 Tamrit, Sefar and Jabbaren area.

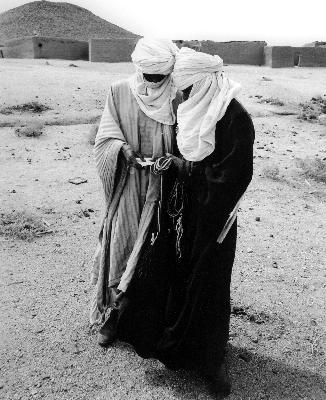

Conclusion

Comparing the characteristics of village life and culture of present day African transhumant pastoralists as represented by the Fulani or Peul, Tuaregs, Boran, Masai, Nuba and other pastoralist groups, with images shown in the prehistoric rock paintings I found many similarities and refer also to Holl, who in his monograph arrived at a similar conclusion. Based on this I concluded that the prehistoric Tassili people were transhumant pastoralists, who moved their livestock between different grazing lands according to season, in the lowlands during the wet season and on the Tassili plateau during the dry season.

NB.

- It should be noted that in spite of the similarities between village life images of the prehistoric Tassili inhabitants and those of traditional rural societies in West Africa of today there is no proof that present day West African traditional rural societies are the direct descendants of the prehistoric pastoralists from the Tassili plateau.

- In spite of this, I propose to conduct detailed studies of present day traditional rural West African societies, which could provide additional information on specific details of village life of prehistoric Tassili pastoralists.

- The rock paintings were probably made during the dry season when the herds of the pastoralists were grazing on the Tassili plateau and movement was more restricted as compared during the rainy season, which would have given artist-pastoralists an opportunity to create their rock paintings.

2.4. A hypothesis on the motivation of the prehistoric pastoralists to create rock paintings.

Studying the rock paintings, I was also struck with the question: What could have been the motivation of the pastoralists to create these rock paintings? Making the paintings must have taken a lot of time and effort, in particular as some images which were up to 6 m high or located in positions, difficult to reach, as for example paintings on cave ceilings.

Reviewing carefully the motifs selected in the rock paintings I concluded that the prehistoric artists had similar motivations as anyone today or whenever during the past who felt the urge to draw pictures. This is a felt need to portray their world and to share this with others, for example with the young generations.

I therefore formulated the hypothesis that the Tassili paintings were made to initiate the young Tassili generations in the important aspects of the pastoralists’ life and that the paintings formed part of the teaching material of the Tassili “bush school”.

In this context, I refer to the West African “bush school” a traditional informal none literate training institution, which was created probably thousands years ago and which in most traditional West African societies was still in use, till recently. Thus all teenage boys and girls of West African tribal societies were obliged to join the “bush” school for a period of time, ranging from several years in the past to only a few months in modern times. These bush schools are far removed from the villages and the teenagers are for the first time in their life separated from their families. In these training camps, tribal elders teach the teenage boys and girls the most important aspects of the tribe’s culture and practical skills such as traditional medicine, hunting, keeping livestock and farming.

Probably at the time of the prehistoric Tassili pastoralists the bush schools were located in the isolated caves on the Tassili plateau and the paintings served as teaching material to explain the pastoralist world. In fact, most of the scenes depicted would fit in very well as teaching material with activities usually undertaken in the African “bush school”.

In conclusion, when studying the extraordinary collection of the Tassili rock paintings, one is struck by the observation that:

- The rock paintings cover a wide range of fascinating aspects of traditional village life, which are rather similar to village life scenes of present day traditional West African tribal rural societies.

- The Tassili rock paintings were probably created with the intention to be used in the initiation of young generations of pastoralists in the African “bush school”.

The Images of the Rock Paintings

2.1 Images by others

2.2 Images from Charles

3. BACKGROUND NOTES

3.1. My 1972 travel through the Sahara and to the Tassili n’Ajjer Plateau

In January 1972, I joined a group of people with similar interests in Sahara travel through Minitrek. This organization made available to us two skilled desert drivers and two Land Rover four-wheel drive vehicles especially reinforced, still required in 1972 for travel on the Sahara tracks. We started our trip in Algiers, which trip would cover about 4500 km by car through the Sahara and about 100 km trekking on foot on the Tassili plateau visiting the prehistoric rock paintings.

In 1972, the road from Algiers to Ghardaia, some 600 km south of Algiers was already paved. The trip from Ghardaia to Tamanrassat and from there to Djanet and back to Ghardadia was on unpaved tracks through the Sahara. Sometimes the track was on flat and hard terrain, allowing speeds of up to 80 km per hour, while at other times the track was very rugged with many rocks, climbing or descending steep rocky hills. Other parts of the track lead through very soft sand dunes and speed was reduced to 10-15 km per hour, whereby the vehicles frequently got stuck in the sand and had to be dug out, using metal sand ladders. In spite of the very poor condition of the tracks, the heavy load of the vehicles: six passengers, luggage, equipment, food, and ten 20 liter jerry cans with water and petrol for each vehicle, no major repairs were needed during our trip, apart from changing occasionally sets of springs on both vehicles. At night we slept in our sleeping bags in the open air, enjoying the beautiful clear sky and watching many stars which one never sees in town. The food was simple but adequate: cvsalg060-066. We enjoyed the fantastic desert landscapes through which we traveled. As my images show, the Sahara landscape has many fascinating features: impressive rock formations, impressive mountain ranges, sand dunes and huge flat areas. There is a wide variety of colors ranging from the dark purple color of some rock formations to the vivid orange colored sand dunes: cvsalg077-109

Our travel route

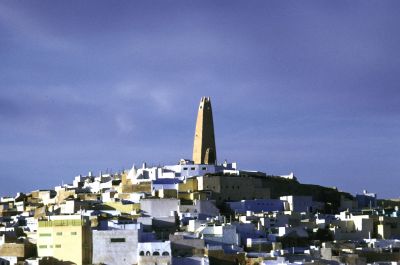

The first stop of our trip was in Ghardaia, a colorful oasis town about 600 kilometers due south of Algers in the Mzab Valley. Ghardaia is the capital of the Mozabites region. It has a very colorful market. The lightskinned Mozabites, are a very orthodox Muslim sect, known as the puritans of the desert. The city was founded in the 11th century by the Kharijites, a special Muslim sect, which fled from the north coast of Algeria to avoid persecution from main stream Muslim sects. The Mozabites dug over 4000 wells in the Mzab Valley, created date palm oases and built five towns which are united in a confideration. Ghardaia was built round a cave inhabited by the female Saint Daia, hence the name Ghar Daia or cave of Daia. The present population of the Mozabites area is estimated at 100 000: cvsalg028-036

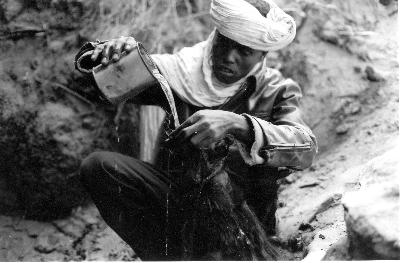

The next stop after Ghardaia was the oasis of El Golea, where we visited a foggara, a system of partly underground canals in a depression. Water is lead through these canals to irrigation basins in which vegetables, fodder and tomatoes are grown. Tree crops of this farming system include date palms, almonds and peaches.cvsals041-054 After El Golea we next stopped in In Salah, a similar oasis as El Golea. Some 150 kilometers south of In Salah we visited the guelta Tiguelguemine. cvsalg069. A guelta is a low laying depression from where water is permanently submerging to the surface. Surprisingly even in the middle of the Sahara one find these gueltas.

After Tiguelquemine we passed Arak gorge, a small oasis located in a very impressive gorge with massive rocks resembling huge castles: cvsalg070-073. We also visited former French foreign legion forts Mirabel: cvsalg 055-056. Polignac and Gardel.

The following stop was Tamanrasset, the capital of the Tuareg tribes, while Berbers are the other main group of inhabitants. The town is located in the Hoggar Mountains, at 1400 m elevation and 2000 km south of Algers: cvsalg077. It is the main trade centre for the central Sahara and produces citrus, peach, apricot, dates, almonds, figs, cereals and maize in its irrigated fields. Camels and goats are the main livestock, while donkeys are used to carry goods.

After visiting Tamanrasset we continued our travel through the Hoggar, a mountainous plateau in southern Algeria. The highest peak, Tahat Mountain, is at 3003 meters elevation. The landscape is rocky and arid with only occasional vegetation, at those locations, where some seasonal rivers cut through the landscape. Our first stop on the Hoggar plateau was at the refuge of Pére Foucauld, a French hermit and student of the Tuaregs, who was killed in 1916 by a Tuareg. The refuge is located at an elevation of 2200 m at the foot of the impressive landscape around mount Assekrem with an elevation of 2700 m: cvsalg074-076

After Assekrem we crossed the Hoggar mountain plateau via Ideles- Herlafak and Fort Flatterscvsalg099. The Hoggar plateau landscape is characterized by fantastic rock formations interspersed by very huge empty stretches of desert: cvsalg077-098. Yet within all this emptiness one day we met a fully loaded truck with passengers and goods traveling from Libya to Niger: cvsalg096. After crossing the Hoggar plateau we arrived in Djanet: cvsalg101-103. Djanet is an oases town south west of the Tassili plateau, inhabited by the Kel Ajjer Tuaregs and is the base from where trips to the Tassili n’Ajjer area usually start.Map:tas002

Trekking on the Tassili plateau

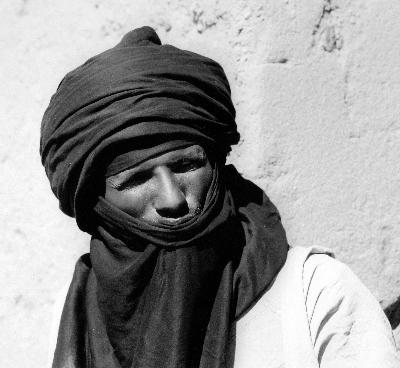

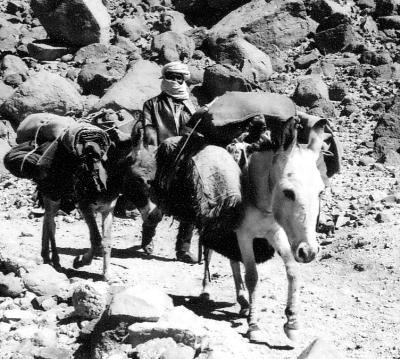

Starting from Djanet, we made a five day walking trip on the Tassili plateau to study the rock paintings created by the prehistoric pastoralists. Our guide was Sermi, a Tuareg: cvsalg155. With him we climbed the plateau via the three passes from Akba Tafilet: cvsalg 110-117 and stayed the first night in Tamrit, while our camping gear and luggage was carried up on donkeys: cvsalg121-133. After visiting the rock paintings in Tamrit we saw the rock paintings in Tin Aboteka, Tin Tazarift and Tin Itinen on our way to Sefar where we stayed the night. The next day we used the entire day to study the many beautiful paintings in Sefar:cvsalg138-142

The day after this we walked from Sefar to Jabbaren which also has a large collection of wonderful paintings. We stayed the night in Jabbaran and returned the next day from Jabbaran via Akba Aroum to Djanet where our vehicles were parked, after a walk of about a 100 kilometer.

The landscape was very beautiful: cvsalg134-152 with very rugged rock formations and deep caves in which we found the rock paintings. Map: tas003

A special note on Jabbaran:

The Jabbaran area, with contains one of the largest collections of rock paintings of the Tassili area, has the form of a large town square closed off with rock walls in which the caves are located. They were probably used as dwellings in prehistoric times. The Jabbaran “town square” measured some 600 by 600 meters. In Jabbaren we visited a large collection of beautiful rock paintings. Many pieces of pottery, grinding stones, arrow piles and other stone tools were found in these caves. The C14 radio- carbon dating analyses, of the campfire remains, indicates that this area was inhabited between 4000 BC and 2000 BC. See map of the Tamrit- Sefar- Jabbaren area: tas003

Continuation of our travel by car through the Sahara

After our visit to the Tassili plateau we traveled north to return to Algiers. Our first stop was the Iherir oasis. This oasis is located in a magnificent landscape bordered by an impressive massive rock wall. Nearby Iherir flows the Wadi Iherir, the only river in the center of the Sahara. Iherirs’ inhabitants own livestock and grow vegetables. They were hospitable people, who offered us tea: cvsalg160-171.

We concluded our trip by crossing the Grand Erg Oriental, one of the Sahara’s largest sand dunes areas: cvsalg104-109. and returned via Fort Flatters, Quargla and Ghardaia to Algers for the flight back to Europe.

The main route taken by Charles and his friends in early 1972

By car:

- Algiers- Ghardaia paved road – 600 km

- Ghardaia – Tamanrassat: 1400 km unpaved desert track

- Ghardaia –El Golea

- El Golea -Fort Miribel- In Salah- Guelta Tiquelquemenia

- In Salah- Gorge Arak- Tamanrassat

- Tamanrassat-Assekrem- Refuge Ermitage du Pere de Foucault-

- Hoggar Plateau-Ideles- Herlafak-

- Herlafak- Fort Gardel – Djanet

On foot: at the Tassili plateau to visit the rock paintings: 100 kms

- Djanet- Tassili N Ajjer plateau

- Akba Tafilalet- Tamrit

- Tamrit- Tan Zoumaitek- Tin Tazarift- Tin Aboteka-Tan Itinen

- Tin Aboteka -Sefar

- Sefar- Jabbaran

- Jabbaran – Tamrit

- Tamrit- Djanet

By car:

Djanet – Iherir

Iherir – Tiguentourine- In Amenas-Grand erg Oriental

Hassi Messaoud-Quargla -Ghardaia- Algiers

3.2 Developments in other parts of the world during the period 4000- 2000 BC.

To provide some background to the developments at the Tassili plateau during the 4000- 2 000 BC period, developments in other parts of the known world, during the same period, are briefly summarized as follows:

During the period 4000 – 2000 BC mankind made rapid progress and it is in this period that in locations with favorable circumstances the transition occurred from the Neolithic period or Stone Age to the Bronze Age. The small traditional societies depen- dent on hunting gathering and simple dry land farming which existed in 4000 BC developed during the fourth millennium into city civilizations with complex community organizations and sophisticated technologies, including the development of writing, the invention of the wheel, mathematics, astronomy, irrigated agriculture and related technologies. References: 6 & 13

Thus, for example by 3000 BC in Uruk, a town in Sumer, South Mesopotamia, present day Iraq, a complex city civilization had developed, based on irrigated agriculture. Writing, book keeping, mathematics, astronomy, medical science and many other technologies, including the invention of the wheel and the making of bronze tools and weapons had been developed. Uruk was trading with locations as far apart as Afghanistan for lapis lazuli, the Indus valley for carmelian, Anatolia and Persia for metal ores, gold and silver and the Zagros and Libanon for cedar wood. Uruk exported to these places grain, leather, dried fish, dates and textiles. Some authors suggest that the Uruk civilization actually established colonies in some of these locations to facilitate and safeguard its trade. Much information is also available about some of the kings of Uruk among whom Gilgamesh is the most famous, as several poems about his adventures have survived till this day.

Also in Egypt similar developments had occurred and by 3000 BC already kingdoms existed in South and North Egypt which in 2 700 BC merged into one country under the First Dynasty. Also here in Egypt writing, the invention of the wheel, astrology, mathematics and irrigated agriculture was already well developed by 3000 BC.

In the Indus valley, in Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, similar developed societies were reported by 2700 BC. The same applies for developments in China in this period. For example, silk cultivation was already well established by about 3 000 BC. In Europe during this period traditional permanent or semi permanent farming systems developed.

When we are discussing the Sahara pastoralists living in the period from 4000-to 2000 BC, it may be useful to realize that we are already talking about modern man, who was gradually developing technologies, tools and equipment to improve his living conditions. Location specific opportunities were different between geographical areas, explaining why pastoralists were living in the stone-age in the Sahara in the same period as highly developed bronze-age civilizations existed in Sumer and in Egypt.

3. Sahara Images

3.1 Desert Towns and Oasis

3.2 Desert Landscapes

3.3. Hypotheses about motivations for creation of the Tassili rock paintings by Lhote, Le Quellec, McKenna & von Daniken

Reviewing the literature, I found that Lhote H, Le Quellec J.L.McKenna T and von Daniken E. had formulated other hypotheses about the motivations of the prehistoric artists to create the Tassili rock paintings.

Lhote assumed that the main reason for producing the rock paintings was for magic purposes based on religious beliefs of the Tassili people. In his opinion, the depicted persons were asking their divinities for assistance for specific purposes such as the healthy birth of babies, a productive herd and luck in hunting. Yet he contradicts himself in other sections of his book where he discusses the images with the herds with cattle, sheep and goats and explains that these are examples of the naturalistic school in which no magic is involved: Ref no 8

Le Quellec assumed in his monograph Rock Art in Africa that the images of rock paintings represented the myths and legends of these prehistoric people: Ref no 7

McKenna assumed that the rock paintings were produced in the context of a lost religion which was based on hallucinogenic mushroom. He saw figures in the rock paintings that were sprouting mushrooms all over their bodies and also found that some images were representing shamans, carrying mushrooms: Ref no 11

Von Daniken saw in the rock paintings images of extraterrestrial beings who had originated from other planets, who had been visiting Earth to bring new technologies: Ref no 16

In my personal view the hypotheses formulated by Lhote, Le Quellec, McKenna and von Daniken all assume motivations which I found rather far fetched and difficult to accept. In section 2.3, I discussed the hypothesis that the Tassili rock paintings were created simply because the artists felt the urge to draw their world vision on the walls of these caves. As the rock paintings were located in remote areas high up in the Tassili plateau these were probably used in the “bush schools” to initiate teenage pastoralist in the important aspects of their society’s life.

3.4. Holls’ analysis method of prehistoric composite rock paintings: The Sahara Rock Art: Archeology of Tassilian Iconography 2004.

Holls’ basic thesis is that “for the most part, the same basic motivations that move anyone to draw pictures existed already in the past. That is, from the very earliest attempts at art, the creator has been attempting to portray his world. Image making involves human minds, techniques, timing, scheduling and location.” (Saharan Rock Art. Page 5)

In Holl’s view, motivation to portray ones world, is often based on a practical reason. In the case of the Tassili paintings he suggests that these sets of rock paintings were made to show all important aspects of the lives of the pastoralists in remote places at the Tassili plateau in “allegorical tapestries of village life” and developed the hypothesis that these pictorial studies were used in the initiation of pastoralist teenager groups to prepare them for the responsibilities of their societies and teach them the collected wisdom, beliefs and practices important to the tribe.

In his monograph, Holl starts the process of analyzing the rock paintings with observing in detail the separate components of specific images and what these present, as well as, their link with other components and other images and then proposes to link these details into sets of interacting images, which illustrate cohesive linked activities. Subsequently he connects these combined sets of images with other sets of images of related activities. After this he combines these series of sets of images into tableaux, which portray parts of the larger allegorical tapestry of village life.

A large composite rock painting located in Iherir was used by Holl to demonstrate his analysis method: This composite rock painting was discovered by Lhote in the Dr Khen Shelter in Iherir during the late 1960s, copied by P. Colombel, a member of his expedition and published in the catalogue for the exhibition in Cologne with the title Sahara: 10 000 Jahre zwischen Weide & Wüste, Museen der Stadt Köln,1978 by Kuper.H. editor, on page 423 & 424. This composite rock painting contains 120 images of humans, 281 images of domestic animals, 47 images of wild life and 66 objects, a total of 514 images which are divided over six acts consisting of different 24 scenes.

The following gives a summary of Holls’ analysis of this composite rock painting from Iherir:

The lives of the pastoralists are ruled by the need to tend their livestock and to move them from one place to another, following the rain and available grazing. As a result, their life is bound to the weather cycles of dry and wet season. This causes the pastoralists to leave their scattered lowland camps, inhabited during the rainy season, for others camps higher up in the mountains, where during the dry season still dependable sources of water are available. During the march from the wet to the dry season camps the herdsmen are alert, to avoid the loss of animals that might wander off or succumb to lions and other predators, yet there is also time for playing games.

In the dry season campsites, the pastoralists set up their huts made of straw mats fixed on a wooden frame and take care of their livestock, including guarding these to avoid predators taking their animals. It is during this period that pregnant women preferably deliver their babies. The dry-season camps in the highlands allow also time to renew friendships with their old friends and relatives from distant parts of the region and for parents to arrange marriages for their sons and daughters, while exchanging gifts with their peers. Teenagers join special groups to be initiated in the responsibilities of adulthood, while during this time the pastoralists also undertake the prescribed rituals to ensure the productivity of their families and their herds.

After the dry season, the pastoralists break up their camps again and split up in smaller groups to find good grazing land for their herds.

The composite Iherir rockpainting thus shows the principal aspect of the pastoralist life, which is keeping and tending of herds of livestock and conducting important social transactions and ritual performances, culminating in celebrations. The story is concluded by images of groups of wildlife. In steps:

- The departure of pastoralist families from their dry season camp

- The arrival of pastoralist families in their dry season camp

- The pastoralist life during the dry season camp

- Marriage and reproduction

- Coming of Age

- Carnival of the animals.

The following scenes are obtained by separating individual scenes from the main composite Iherir rock painting to visualize the “allegorical tapestries of village life” mentioned by Holl in his analysis method. The following images are included in my photo gallery as tas031-047:

tas031: A herd of giraffes

tas032: A group of wildlife including two elephants, an ostrich and some gazelle

tas033: An extended family of pastoralists is traveling with their cattle to their dry

season camp at the Tassili plateau

tas034: The family arrives at their dry season camp

tas035: Goods are unloaded

tas036: The household goods are sorted out

tas037: A hut is constructed

tas038: The cattle are watered at the drinking site near the river

tas039: A young herdsman plays a flute for his sheep, while an older person, in a special costume attends. Possibly a shaman?

tas040: Some young men climb a tree to pick fruits while others watch the cattle which are grazing

tas041: A group of young men with spears is hunting a lion, which has killed several of their sheep.

tas042: In a hut a baby is born

tas043: A herd of sheep and herdsmen. One herdsman holds a newly born lamb, which is not yet strong enough to walk on its own.

tas044: Two elaborately dressed ladies sit in front of their hut and look at a large earthenware container in front of them. A young man carries a similar large earthenware container to a group of sheep. The scene may possibly represent a specific ritual.

tas045: An erotic dance? A similar dance was observed among a Nuba tribe in West Sudans, whereby in a special dance, teenage girls selects the boy of their choice at the end of the dance, by lifting her leg on the shoulder of her favorite boy friend, in a similar way as is shown in this image from Tassili.(Riefensthal)

tas046: Village meetings: One lady receives a group of young people in front of her hut Another lady, sitting on a stool, in front of another hut is waiting for visitors. The lady in front of the third hut is receiving a couple of children, while her dogs are playing. In front of the three huts we see a herd of sheep and goats.

tas047: Represents the composite rock painting from which the above individual scenes were taken, with the exception of the two wild life scenes which were taken from another nearby painting in the same Iherir cave.

In Holls’ view, in this composition the artists have portrayed an overview of proper behavior and conduct necessary for the continued existence of the tribe as a social and economic group. The entire composition presents thus a narrative, tying the contents of the murals into a comprehensive parable, an allegory entertaining and educating Tassilian youths on their personal transhumant journeys to adulthood. Accepting Holls’ interpretation, the murals can be read as a single narrative, a flow of tale-telling progressing from right to left showing the cyclical life of the Tassilian herdsmen and their families and herds and at the same time showing the essential patterns of reproduction in Tassilian pastoralist communities.

These images were copied with permission from Dr Holl, whose permission is herewith gracefully acknowledged: Holl A.F.C. 2004.Saharan Rock Art: Archeology of Tassilian Pastoralist Iconography. Altamira Press, Walnut Creek USA, African Archeology Series. These images are protected by copyright.

4. REFERENCES

- Gardi.R. 1967, Sahara, G G. Harap & Co, London

- Heseltine N. 1959, From Libyan Sands to Chad. Museum Press Ltd, London.

- Holl A.F.C. 2004, Saharan Rock Art, Archeology of Tassilian Pastoralist Iconography Altamira Press, Walnut Creek CA. USA

- Kuper.H. 1978 Sahara: 10 000 Jahre zwischen Weide & Wüste Cologne Museen der Stadt (Art work by P. Colombel and Y. Martin

- Lajoux Jean- Dominique, 1963, The rock paintings of Tassili, World Publishing Company, Cleveland, USA

- Leick Gwendolyn.2001,Mesopotamia The Invention of the City. Penguin Books

- Le Quellec, Jean-Loic., 2004, Rock Art in Africa, Flammarion, Paris, France

- Lhote H. 1958, A la Dếcouverte des fresques du Tassili, Editions Arthaud, Paris.

- Lhote H. 1959. De Rotstekeningen in de Sahara, Sijthoff, Leiden, Netherlands

- Lhote H. 1973. The search for the Tassili Frescoes, Hutchinson & Co. London

- McKenna.T. 1993. True Hallucinations, Harper San Francisco

- Nomachi Kazuyoshi, 1978, Sahara, Westbridge Books Brunel House, Newton Abbot

- Past Worlds, 2003, Collins Atlas Of Archeology, Scarre C.Editor

- Riefenstahl Leni, 1976.The people of Kau. Collins London

- The African Nomad p 405-418 in: Animal Husbandry in the Tropics 1959 Williamson G & W.J.A Payne, Longmans London

- Von Daniken, E. 2002.Extraterrestrial Visitations